064 Somme Road Upper Hutt, Junction leading to Heretaunga Station 2018

Reason for the name

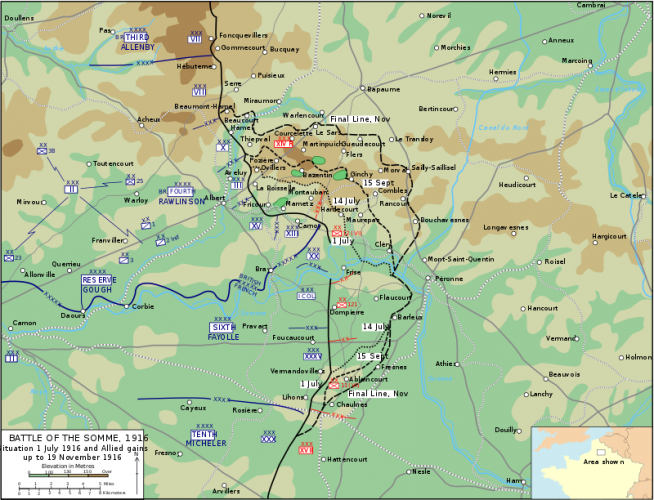

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme, German: Schlacht an der Somme), also known as the Somme Offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and France against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 November 1916 on both sides of the upper reaches of the River Somme in France. The battle was intended to hasten a victory for the Allies and was the largest battle of the First World War on the Western Front. More than three million men fought in this battle and one million men were wounded or killed, making it one of the bloodiest battles in human history.

David Frum opined that a century later, "'the Somme' remains the most harrowing place-name" in the history of the British Commonwealth.

Somme Road is in the suburb of Silverstream and is situated amongst a series of military roads around Trentham Military Camp.

Eighteen thousand members of the division went into action on the Somme. Nearly 6000 men were wounded and more than 2100 lost their lives. Over half New Zealand‘s Somme dead have no known grave – their names are on the New Zealand Memorial to the Missing in Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, near Longueval. New Zealand brought one of these men home in November 2004; his remains lie in the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in the forecourt of the National War Memorial in Wellington.

Author: Poppy Places Trust

The Battle of the Somme

The French and British had committed themselves to an offensive on the Somme during Allied discussions at Chantilly, Oise, in December 1915. The allies agreed upon a strategy of combined offensives against the Central Powers in 1916, by the French, Russian, British and Italian armies, with the Somme offensive as the Franco-British contribution. Initial plans called for the French army to undertake the main part of the Somme offensive, supported on the northern flank by the 4th Army of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). When the Imperial German Army began the Battle of Verdun on the Meuse on 21 February 1916, French commanders diverted many of the divisions intended for the Somme and the "supporting" attack by the British became the principal effort.

The first day on the Somme (1 July) saw a serious defeat for the German 2nd Army, which was forced out of its first position by the French 6th Army, from Foucaucourt-en-Santerre south of the Somme to Maricourt on the north bank and by the Fourth Army from Maricourt to the vicinity of the Albert-Bapaume road. The first day on the Somme was, in terms of casualties, also the worst day in the history of the British army, which suffered 57,470 casualties. These occurred mainly on the front between the Albert–Bapaume road and Gommecourt, where the attack was defeated and few British troops reached the German front line. The British troops on the Somme comprised a mixture of the remains of the pre-war regular army; the Territorial Force; and Kitchener's Army, a force of volunteer recruits including many Pals' Battalions, recruited from the same places and occupations.

The battle is notable for the importance of air power and the first use of the tank. At the end of the battle, British and French forces had penetrated 10 km (6 mi) into German-occupied territory, taking more ground than in any of their offensives since the Battle of the Marne in 1914. The Anglo-French armies failed to capture Peronne and halted 5 km (3 mi) from Bapaume, where the German armies maintained their positions over the winter. British attacks in the Ancre valley resumed in January 1917 and forced the Germans into local withdrawals to reserve lines in February, before the scheduled retirement to the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenberg Line) began in March. Debate continues over the necessity, significance and effect of the battle.

|

Somme casualties |

|||

|

Nationality |

Total |

Killed & |

POW |

|

United Kingdom |

350,000+ |

- |

- |

|

Canada |

24,029 |

- |

- |

|

Australia |

23,000 |

|

< 200 |

|

New Zealand |

7,408 |

- |

- |

|

South Africa |

3,000+ |

- |

- |

|

Newfoundland |

2,000+ |

- |

- |

|

Total British |

419,65 |

95,675 |

- |

|

French |

204,25 |

50,756 |

- |

|

Total Allied |

623,907 |

146,431 |

- |

|

Germany |

465,000–600,00 |

164,055 |

38,00

|

After a period of rest and reorganisation following the Gallipoli evacuation, the newly formed New Zealand Division left for France in early April 1916. Sent to the Flanders region to gain experience of new trench conditions, they spent the next three months guarding a ‘quiet’ sector of the line at Armentières before moving south to the Somme battlefields and their first large-scale action on the Western Front.

A truly nightmarish world greeted the New Zealand Division when it joined the Battle of the Somme in early September 1916. The division arrived to take part in the third big push of the offensive, designed to crack the German lines once and for all. When it withdrew from the line a month later, a decisive breakthrough had not been achieved.

Eighteen thousand members of the division went into action. Nearly 6000 men were wounded and more than 2100 lost their lives. Over half New Zealand‘s Somme dead have no known grave – their names are on the New Zealand Memorial to the Missing in Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, near Longueval. New Zealand brought one of these men home in November 2004; his remains lie in the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in the forecourt of the National War Memorial in Wellington.

The battle was a pivotal event in the Great War. In retrospect, it laid the basis for the Allied victory two years later, though at huge cost. Ten decades on, the numbers still have the power to shock. At the end of 4½ months of fighting, some 1.2 million men were dead or wounded; about 8500 casualties for each of the 141 days of conflict. Some days were especially costly. The opening day of the offensive, 1 July 1916, was arguably the worst day in British military history: 19,000 men were killed and another 38,000 wounded. By the end of the campaign on 18 November 1916, the Allies had advanced, at most, 10 km into German-held territory – a distance a fit young man can run in less than an hour.

New Zealand artillery on the Somme, 1916

At 6.20 a.m. on 15 September 1916, the boom of more than a thousand guns heralded the beginning of the new big push on the Somme. Amidst this awesome array of firepower were four brigades of the New Zealand divisional artillery. Deployed just three days before, these field gunners had the task of helping the infantry cross the battlefield and protecting them once they reached their objectives. Two brigades supported the New Zealand infantry, while the other two supported British infantry to their right.

In the preceding days, the New Zealand gunners had concentrated on preparing gun positions for the advance. Barbed-wire entanglements protecting enemy trenches had been targeted, while the longer-range howitzers blasted trenches, lines of communication, machine-gun nests, observation posts and other strongpoints. On 12 September, New Zealand gunners fired poison-gas shells for the first time.

Airmen in balloons or aircraft or forward observation officers – artillery officers stationed in the front line – called down concentrated fire from groups of batteries (later called ‘crashes’) on anything that moved around the German lines, while British heavy guns sought out enemy batteries. At 6 p.m. on the 14th a continuous heavy bombardment began.

At 6.20 next morning, field guns attached to the New Zealand Division opened fire along the 900 m of enemy trench line that was the infantry’s first target. Enemy troops who had been kept awake all night by the preliminary shelling – and were now terrified at the prospect of imminent attack – took cover from a rain of steel that lasted for minutes but felt like hours. Then the creeping barrage began, starting in no-man’s-land and lifting (advancing) by 45 m each minute until it reached the second trench line, which was pounded for some time. In large-scale attacks like this one, a combination of stationary and creeping barrages was repeated several times.

The Allied infantry advanced just behind the creeping barrage, sometimes having to wait for it to lift forward. ‘Friendly fire’ casualties were regarded as inevitable. Laying errors, defective shells, worn gun barrels – all could lead to shells falling short. Attacking troops advancing too quickly sometimes entered the curtain. These were considered acceptable risks, for if the men were not following the creeping barrage closely when it reached the enemy line, machine-gunners would inflict far more casualties than the occasional drop-short shell. As the troops approached the enemy line, the stationary barrage lifted to the line behind and the creeping barrage swept over the trench with the troops right behind, leaving the defenders no time to man their machine guns. Men with bayonets were soon in the trench among them.

On this morning, the attack plan worked well. The attacking infantry were shielded as they approached their initial objectives — Crest Trench and, 230 m beyond, Switch Trench — and the defenders were bayoneted, taken prisoner (not many) or shot as they fled. The artillery then shifted to the main objective, the Flers Trench system, while the leapfrogging riflemen carried on the advance without a creeping barrage. When uncut barbed wire held them up at one point, a tank quickly opened the way by crushing this and Flers Trench was seized. Next morning the gunners broke up a counter-attack before helping the infantry take their final objective, Grove Alley.

Following the 15 September attack, the artillery continued to play an active role in the battle. A deluge of shells usually broke up German counter-attacks before they got near the New Zealanders’ lines. Forward observers called this fire down from observation posts close to the line. On three further occasions before the New Zealand infantry withdrew, the gunners carried out fire-plans to support assaults.

The gunners remained in the line when the New Zealand Division was withdrawn on 5 October. For another three weeks, they toiled over their pieces, often under bombardment with little cover. It was a miserable time for the gunners, who were often soaked, cold and hungry.

There was relief, therefore, when they too were pulled out in the last week of October 1916. By this time, more than 500 of them had become casualties. In all, the New Zealand gunners had fired half a million shells at the Germans.