055 Montgomery Street Hastings, street view 2017

Reason for the name

Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery was in command of all Allied ground forces during Operation Overlord from the initial landings until after the Battle of Normandy. The proximity to Freyberg St is appropriate, as Freyberg was referred to by Montgomery as his best field commander, and they both were heavily involved in the successful battle of El Alamein in WWII, in October 1942.

In 1951, Montgomery became deputy commander of the Supreme Headquarters of NATO, serving for seven years. This increased his profile, at the time when further subdivision in the area adjoining Freyberg St was to happen.

Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery was in command of all Allied ground forces during Operation Overlord from the initial landings until after the Battle of Normandy

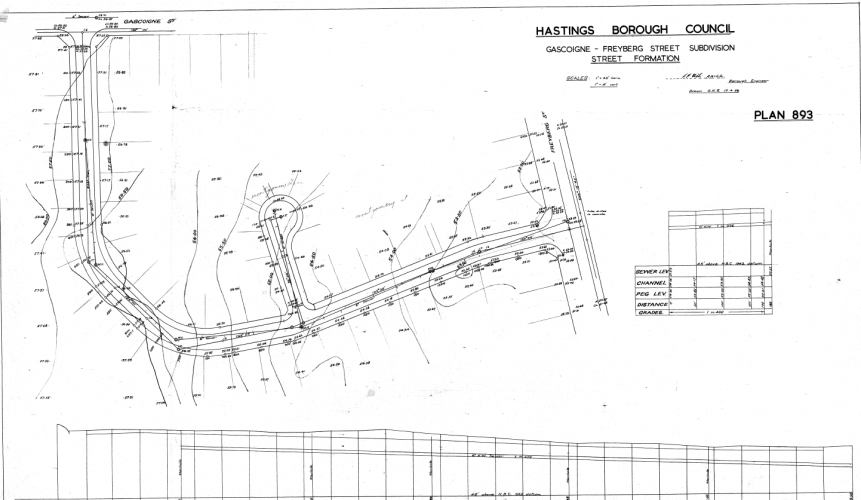

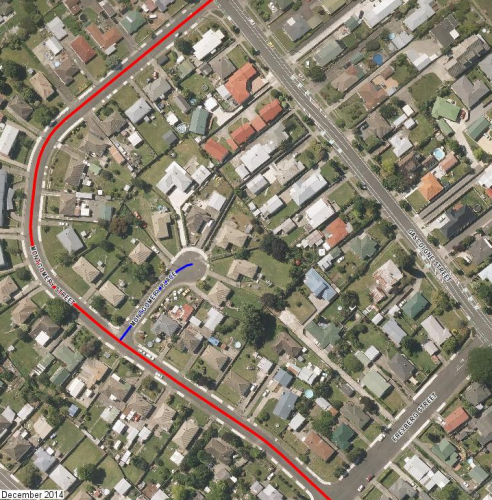

The Gascoigne - Freyberg Street subdivision plans were done in 1956, and created Montgomery Street and Montgomery Place between Gascoigne St and Freyberg St.

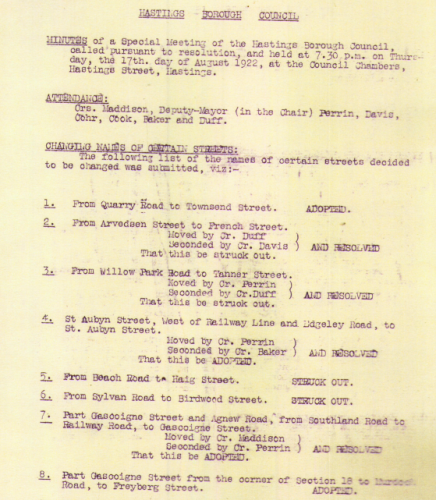

Freyberg Street was named in 1922, when a resolution was made to rename that part of (what had been) Gascoigne Street to Freyberg Street.

Author: Cherie Flintoff HDC

Bernard Montgomery, or “Monty”, was born in London in 1887, one of nine children of Reverend Henry Montgomery and his wife Maud. He started life in Northern Ireland and had a strict upbringing. His father was made Bishop of Tasmania in 1889.

When his father got a posting in London and returned to Britain in 1901, Montgomery attended St. Paul's School before entering the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Graduating in 1908, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and assigned to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Sent to India, he served abroad until 1913. With the outbreak of WW1, Montgomery deployed to France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

In October 1914, at the First Battle of Ypres, Montgomery, a young lieutenant, was shot through the lung and nearly died. This wound led to an ongoing aversion to smoking. He received the Distinguished Service Order (an unusually high distinction for a junior officer) and was later appointed as a brigade major.

He later served in training and staff postings and during this time he became known as a meticulous planner who worked tirelessly to integrate the operations of the infantry, engineers, and artillery.

After commanding a battalion of occupation forces, Montgomery reverted to the rank of captain in November 1919.

Moving through a variety of peacetime postings, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1931. Between the wars he served in India, Egypt and Palestine, as well as taking part in the Irish War of Independence.

Monty married a widow Elizabeth (Betty), the sister of a fellow officer, in July 1927. They had happy years, and a son David, together, before she died in 1937 of septicaemia as a complication of an infected insect bite.

Throwing himself back into work, in 1938 he organized a massive amphibious training exercise that was praised by his superiors and was promoted to Major General.

With the outbreak of WW2 in September 1939, his division was deployed to France. Fearing a disaster similar to 1914, he relentlessly trained his men in defensive manoeuvres and fighting.

In August 1942, Montgomery was elevated to Commander of the Eighth army in Egypt. Britain had thus far always been on the back foot in the war. In the African theatre, Monty’s adversary Rommel was gaining near mythical status (amongst both German and British soldiers) about his seeming invincibility.

The New Zealand Division played a key role in the second Battle of El Alamein, which began on 23 October 1942. While the New Zealanders seized their objectives, the overall battle did not develop as Montgomery expected. Congestion, poor coordination and cautious leadership prevented Allied armoured units from taking advantage of gains made by the infantry.

Montgomery planned a new attack – Operation Supercharge – further to the south, which would essentially repeat the process of the initial attack. He looked to the New Zealand Division's experienced headquarters to plan the ‘break in’ component of Supercharge, although the division itself was too weak to provide the necessary punch. Two British brigades, with New Zealand support, would carry out the attack while New Zealand infantry battalions protected their flanks. Following the breakthrough at El Alamein the New Zealand Division reached the Libyan border by 10 November 1942. It seized Halfaya Pass, taking 600 prisoners in the process, before being pulled out of the line.

After recuperating near Bardia, the New Zealand Division moved forward to the front at El Agheila in December. The New Zealanders made a series of attacks inland in an to attempt to cut off the Afrika Korps but Rommel’s forces managed to slip away on each occasion.

On 6 March New Zealand artillery help stop a German counter-attack at Medenine. This would be Rommel’s last action in North Africa – three days later he returned to Germany on sick leave. The 8th Army now prepared to attack the Mareth Line. Montgomery’s plan was for the recently formed New Zealand Corps, reinforced by British and French units, to push south to Tebaga Gap and encircle the German-Italian forces busy fighting the main Allied assault on the Mareth Line.

The New Zealanders reached Tebaga Gap on the night of 20 March. While they managed to capture several Italian positions a cautious Freyberg did not press home the assault immediately and the opportunity for a quick victory was lost. The stalemate was broken with a carefully planned and well-executed attack on 26 March. Operation Supercharge II began with a combined artillery barrage and low-level air attack. An infantry and armoured assault then shattered the enemy defences at Tebaga Gap. Despite the breakthrough, savage fighting continued to the south around Point 209, where the 28th (Maori) Battalion were positioned. It was here that 23-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngarimu won a posthumous Victoria Cross (VC) – the first by a Maori serving with the New Zealand forces.

Monty worked hard to raise morale among the forces and to unite land, naval, and air units into an effective combined arms team. He was able to deliver a successful counter attack against the Axis forces in October – November 1942. It was a decisive victory for the Allies and was celebrated back home. It was said that before El-Alamein we never had a victory, but after El-Alamein we never had defeat. It was not quite as simple as that, but it was a crucial turning point in the balance of power in the Second World War.

This famous victory elevated the status of Monty. He already had a certain ‘cult’ status amongst the mass of army recruits. They admired his unorthodox habits like the way he dressed and his disdain for military procedures. After El-Alamein, he became a major celebrity in Britain and crowds would often flock to great him.

Knighted and promoted to general for the victory, he maintained pressure on Axis forces and turned them out of successive defensive positions including the Mareth Line in March 1943.

Next came planning for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The campaign was a success, but Monty’s style clashed with his flamboyant American counterpart Lieutenant General George S Patton. The British and American forces then began a slow, grinding advance up the Italian peninsula.

On December 23, 1943, Montgomery was ordered to Britain to take command of the 21st Army Group - all of the ground forces assigned to the invasion of Normandy. He played a key role in the planning for D-Day and oversaw the Battle of Normandy after Allied forces began landing on June 6. He was criticised for the long delays in managing to take the city of Caen and for the large tank losses in a campaign that followed, with other contributing factors being poor intelligence about the Axis strength and armaments and heavy rain.

On December 16, the Germans opened the Battle of the Bulge with a massive offensive. With German troops breaking through the American lines, Montgomery took command of US forces that had been cut off on the north. He was effective in this role and was ordered to counterattack in conjunction with Patton's Third Army on January 1 with the goal of encircling the Germans. Not believing his men were ready, he delayed two days allowing many of the Germans to escape. Pressing on to the Rhine, his men crossed the river in March and helped encircle German forces in the Ruhr. Driving across northern Germany, Montgomery occupied Hamburg and Rostock before accepting a German surrender on May 4.

Monty was well known for taking care of the troops in his command. However, he was not known to be modest and is reputed when asked which three generals he admired most to have replied “the other two would be Alexander the Great and Napoleon.”

After the war, Montgomery was made commander of the British occupation forces and served on the Allied Control Council. In 1946, he was elevated to Viscount Montgomery of Alamein for his accomplishments.

On 16th July 1947 Lord Montgomery arrived in New Zealand to confer with the Government on defence matters. He toured the country, receiving a hero’s welcome everywhere he went. Public servants in central Wellington were granted an hour’s leave so they could witness the Field Marshal’s drive from Government House to the Cenotaph, where he laid a wreath.

Serving as Chief of the Imperial General Staff from 1946 to 1948, he struggled with the political aspects of the post. Beginning in 1951, he served as deputy commander of NATO's European forces and remained in that position until his retirement in 1958.

Montgomery died on March 24, 1976, and was buried at Binsted.