124 McGregor Street Palmerston North, street scene 2017

Reason for the name

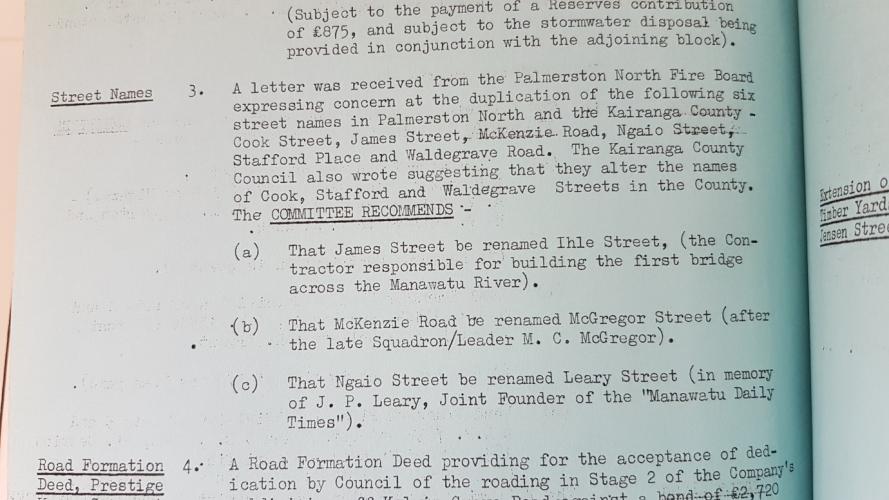

This suburban street in Milson was named in honour of the late Squadron/Leader M C McGregor after the Palmerston North City Council passed a resolution on 9th June 1966 to change the name from McKenzie Road.

Originally part of Section 528 in the Kairanga County, McGregor Street was first known as McKenzie Road and developed in the 1920s. The street was named after Roderick A. McKenzie who was one the property owners in the locality and was widely known as a patron of horse racing and one of the largest cattle owners in the North Island. McKenzie also sold to the Government large blocks of land off Newbury Line as part of the Returned Soldiers Settlement scheme post-WWI, a road which also bore his surname.

Confusion around McKenzie Road in Milson being similar to McKenzie Settlement Road in Kairanga led to requests for a name change to the Council. In 1966 the Palmerston North City Council acted upon a request to change the name of McKenzie Road. As the aerodrome, which was undergoing expansion at the time, terminated at the road, the Council saw fit to bestow upon it a name associated with a local flying personality, namely the late Squadron Leader M C McGregor.

McGregor Street runs west to east, starting at Milson Line, before dog-legging north and ending at Airport Drive. The street served as a main road for other property developments in the area: Terry Crescent, Pinedale Parade, Paradise Place, and Palliser place throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Other amenities in the area include the Mahanga Kakariki and Clearview reserves, as well as Palmerston North Airport.

Author: Evan Greensides, Heritage Assistant for Palmerston North City Libraries & Community Services.

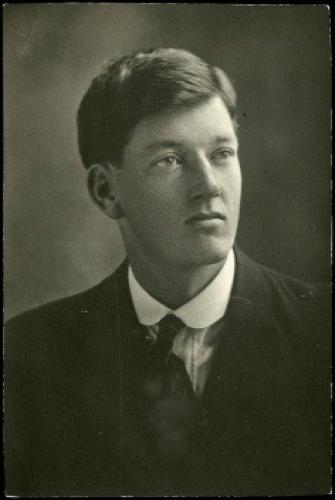

History of Squadron Leader Malcolm Charles McGregor

Born in Mangamako near Hunterville in the Manawatu-Whanganui region on 4 March 1896, Malcolm Charles McGregor was the youngest of three children born to sheep farming parents Ewen and Matilda McGregor (née Chubbin). Initially refused parental permission to enlist in the army during the First World War, McGregor turned to writing to the adjutant-general of the New Zealand Defence Force, stating,

As I am only 19 ½ years of age and my parents will not allow me to go to the trenches till I am 21, I am anxious to serve my country, and my ambition is to join the Flying Corps. Could you please supply me with full particulars of which course to follow. Is it necessary for me to apply to the Flying School, Auckland, or through the Defence Recruiting Officer?... Please pay this matter your utmost urgent attention as I am anxious to join the Flying Corps straight away.

With the Defence Department unable to help, McGregor entered Leo and Vivian Walsh's New Zealand Flying School at Mission Bay, Auckland, qualifying on 9 September 1916. Soon after he sailed for England aboard the Willochra.

Following 3 months of advanced training with the Royal Flying Corps, McGregor was posted as a fighter pilot to No 54 Squadron in France. After seeing limited action in the air above the battlefield, on 29 June McGregor’s Sopwith Pup engine failed, unbalancing the machine and forcing him into an emergency landing along the pockmarked front lines. Hitting a crater and overturning, McGregor’s head smashed into his machine-gun, knocking out his teeth and fracturing his jaw. A lengthy recovery in hospital ensued.

While McGregor was put into a flying instructor role after exiting hospital, he soon found these duties frustrating compared to the excitement of fighter pilot endeavours. Over this time period he was reprimanded for performing such stunts as chasing a train, attempting to remove a windvane from a church spire with his propeller and terrorising a local town with ever more dangerous acrobatics. During a daring “buzzing” of Buckingham Palace and low down the Thames River, McGregor noted,

It was a glorious evening and there were crowds punting and rowing. We flew along a few feet above their heads, taking the bends in great style and turning back to see any extra pretty girls... Got off with a severe reprimand. Plonk!

Ever the amuser, one morning McGregor lost his false teeth. Concerned that no one would be able to understand him if shot down, McGregor, to the great delight of his squadron, refused to fly until they were found.

McGregor returned to France in May 1918 and was posted to No 85 Squadron of the recently established Royal Air Force. Commanded by Canadian ace Billy Bishop and flying SE5a fighters throughout the final offensives of the war, McGregor was promoted to captain on 22 July and given command of his own flight. The recommendation for the Distinguished Flying Cross described McGregor as “a pilot of exceptional, even extraordinary skill… a clever leader, full of resource and dash.” He was awarded the DFC and bar, and was credited with downing 10 enemy aircraft and an observation balloon.

McGregor gave an insightful account into actions which took place in the aerial battlefield above the trenches, stating,

Once you find the lines (and you do that by flying east until you are shot at), it is wonderful the good that can be done by helping the infantry, knocking out machine guns, shooting up troops and transport etc. Whenever an aeroplane flies low over hostile troops, it seems to be the craze for anyone with anything that will shoot to let blaze… [put] a hole in my pal’s leg from an explosive bullet. Plucky little beggar, after being hit he turned back into Hunland and dropped his bombs on the people that fired at him, all on one of the worst days an aeroplane had flown.

However, back at No 85 Squadron’s airfield the need to inject a bit of humour into the bleak landscape around them led to the unit collecting a vast menagerie of animals. It was expected that every officer was to have a pet, an unwritten rule which had started when the unit smuggled 4 chow puppies across the Channel. Every animal from then on was fair game - the unit soon after possessed “a motley collection of assorted dogs, goats and even poultry”. McGregor, after being shot down inside Allied lines and waiting for a staff car to pick him up and return him to the airfield, kidnapped a nanny goat. Arriving back at base, he justified the presence of the new pet as being able to provide the squadron with milk for their cups of tea.

On the evening of November 10, as word quickly spread that there would be peace the next day, Malcolm was dining with others from the squadron in the mess tent when a mechanic burst in, stating, “they are signing the Armistice tomorrow, and there will be no more war.” Malcolm feigned throwing a glass at the mechanic and stated, “Out of this, you blighter, and take your dismal news with you”. McGregor returned to New Zealand in August 1919 aboard the Bremen, returning to his parents' Waikato property and undertaking farm work before purchasing his own dairy farm at Taupiri. The farm proved difficult to sustain in the harsh economic conditions of the early 1920s, however, and Malcolm reluctantly disposed of it in 1925. Malcolm returned to his father's new farm at Rukuhia, near Hamilton, managing the business there. While at Rukuhia, McGregor met Isabel Dora Postgate, a law clerk, and the two were married on 29 July 1925 at Frankton Junction. Malcolm and Isabel had two sons and two daughters. In 1927, Ewen McGregor sold the farm, and Malcolm worked as a drover for the next two years around the area. McGregor's passion, however, remained with aviation, and after his father’s farm sold he returned to the sector.

Malcolm was a founding member of the New Zealand Air Force (Territorial) in 1923, was promoted to squadron leader and appointed commanding officer of No 2 (Bomber) Squadron in 1930. Malcolm had earlier been granted a commercial pilot's licence and formed Hamilton Airways when he acquired a single de Havilland Gipsy Moth. While his military career had proved successful, Malcolm’s later commercial ventures did not fare so well. In 1930 he was technical director of the short-lived National Airways (NZ), operated a Gipsy Moth named 'Chocolate Plane' for Cadbury Fry Hudson Limited and, in partnership with Maurice Clarke, formed Air Travel. Although the main revenue stream was through operating a regular Christchurch–Dunedin service, the company survived up until 1932 chiefly through other means such as joyriding, parachuting and experimental airmail flights.

In late 1932 McGregor relocated to Palmerston North after he secured regular employment as chief flying instructor for the Manawatu Aero Club. This was interrupted, however, by a lengthy hospital stay after a flying accident in December where he crashed during a competition in which pilots had to burst hydrogen balloons with their propellers. After his recovery, Malcolm and Henry Walker entered the London to Melbourne Air Race in 1934, flying a Miles Hawk aircraft named “Manawatu” which was owned by the Manawatu Centenary Air Race Committee. The plane ended in fourth position in the handicap race, with their achievement creating a large amount of public interest in aviation. Returning home, both men toured the country, displaying the famous aircraft. Malcolm was also one of the first pilots of Union Airways of NZ Ltd., which was the first commercial airline to operate from Palmerston North.

Malcolm died at the age of 39 when his aeroplane crashed at the Wellington Aerodrome on 19 February 1936. The accident was caused by the aeroplane’s right-wing clipping the mast of an anemometer while descending, with the weather at the time being described as “misty, rain was falling and the visibility was thus considerably impaired”. Two days later, he was transported back to Palmerston North and given a full military funeral, with a commemorative service being held at the Opera House before burial. Malcolm’s popularity to the New Zealand public was demonstrated by the extraordinary response to a national appeal launched immediately after his death, raising over £5,000 to support his widow and their four young children. Malcolm Charles McGregor is buried at Kelvin Grove Cemetery, Block 7, Plot 74.