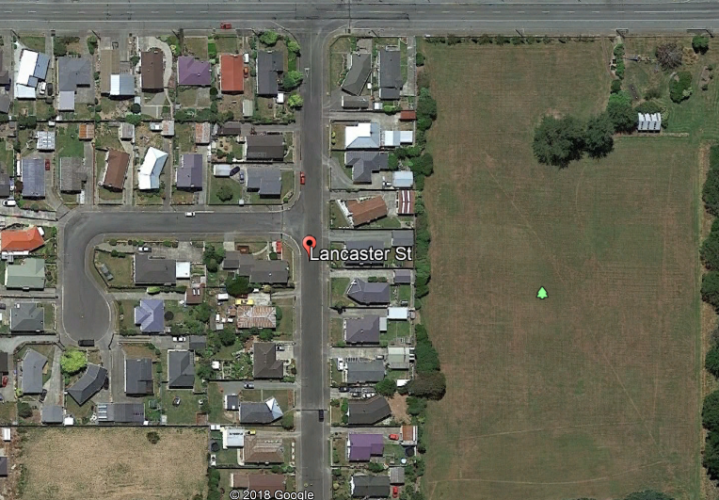

086 Lancaster Street Invercargill, street scene 2017

Reason for the name

Named after the Lancaster bomber flown by NZ Airmen during WW2 whilst stationed at Mepal. The Avro Lancaster is a British four-engined Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to the same specification, as well as the Short Stirling, all three aircraft being four-engined heavy bombers adopted by the Royal Air Force during the same WW2 era

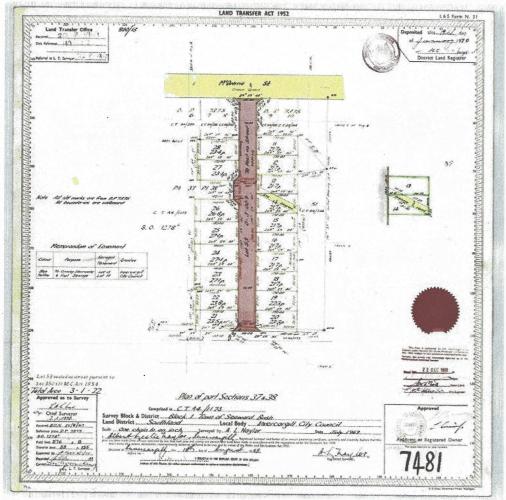

Mepal Place and Lancaster Street Invercargill were developed by Southern Equities Ltd in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Ivan Carroll, Arthur Diack and Louis Crimp were the directors. Carroll and Diack chose the street names based on their WW2 experience as pilots of fighter bombers. Ivan Carroll had been based at Mepal Air Force base, Cambridgeshire, England. New Zealand Defence Force Personnel Archives staff has confirmed that: NZ4213254 Flying Officer Ivan Sylvester Carroll RNZAF NZ Bomber Command 75 Squadron was based at Mepal in England where he flew the Avro Lancaster, a British four-engine 2nd World War heavy bomber. And that: NZ4214077 Flying Officer Arthur Francis Diack 626 Squadron was based at Wickenby Lincolnshire, England, where he also flew the Avro Lancaster on operations.

The Spitfire fighter is the symbol of the 1940 Battle of Britain – the image of fearless fighter aces flashing about the sky in a last ditch effort to keep the enemy out of England will endure, but the key front line weapon in the war in Europe was a much more ponderous craft – the Lancaster bomber.

Author: Poppy Places Trust and Wendy McArthur, Archives Assistant Invercargill City Council

The Lancaster Bomber

Between 1942 and the end of the war, formations of Lancasters, laden with thousands of pounds of bombs, took part in night bombing offensives against Germany’s major cities. The aim of operations was to make the major German cities uninhabitable, and to destroy the morale of the enemy civilian population, especially the industrial workers

The Lancaster’s finest hour (at least, in popular imagination), the famous “Dambusters” raid by 617 Squadron to destroy hydroelectric dams in the industrial heart of Germany in 1943, using a specially-designed bouncing bomb released at low altitude, showed the world that the British had the will and means to fight on.

The Lancaster was the backbone of RAF Bomber Command. It could fly further and higher, carried a greater bomb load, flew more sorties and inflicted greater damage than any other RAF bomber. The Lancaster was the brainchild of design genius Roy Chadwick. In 1941, aircraft manufacturer Avro in Manchester employed 40,000 people – mostly women – to build Lancasters. The conditions of work for women back then were very different from today.

Nearly 8000 Lancasters were produced. The bomber was powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The Merlin was one of the world’s most reliable aircraft engines. Flight Lieutenant Jack t’Hart’s new Lancaster flew faultlessly through 22 ops and always got the crew home. It had a ton of power, which kept them out of trouble, said Jack, even on the notorious Nuremburg raid in 1944, when 95 of the 779 Lancasters were shot down, and 745 airmen were killed, captured, or injured.

The Lancaster had three machine-gun turrets and a crew of seven, and could carry a bomb load of up to 18,000lbs. Toward the end of the war, a common payload was the terrifying 12,000lb Tallboy bomb. The most famous Tallboy ‘kill’ – involving New Zealander Arthur Joplin and his crew from 617 Squadron – was the German battleship Tirpitz, sunk in a Norwegian fjord by Lancasters in 1944.

Lancasters carried out 156,000 missions during the war, dropping more than 600,000 tons of bombs. However, there was a high price – during four years of active service, 3249 Lancasters were lost in action, and 487 were destroyed or damaged while on the ground. A mere 24 aircraft completed 100 missions.

Conditions for the crew were challenging. It was cramped, noisy, unpressurised and very cold. Flight Engineer Harry Cammish said of his first op in a Lancaster: “Nothing prepares you for the reality. Noise, light, bangs, whoomps, thumps. I felt it best to keep busy filling in the log sheet calculating petrol consumption, and not looking out.”

Mid-upper gunner Harry Furner gives an idea what it was like to come under fighter attack, with nothing but a perspex dome for protection: “Most of the perspex in my turret was shattered, hydraulic pipes punctured, and I was blinded in both eyes by the perspex. I also received various shrapnel wounds to my arms and legs – in all, a bit of a mess.”

The four-engined bomber was a big target, not very agile, and easy to hit. The German fighters had powerful cannon and a radar screen on which they could see their target on the darkest night. The only defence a bomber had when attacked from astern was the four machine guns in the rear turret. Lancaster rear gunners, including New Zealand veteran Tom Whyte (101 Squadron), had one of the loneliest jobs in the War. Their casualty rates were always high.

Following the formation of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) in 1937, Kiwis who wanted to be airmen underwent Initial Training, then to Elementary Flying Schools to train in the Tiger Moth aircraft. The “graduates” of the first New Zealand training schemes saw action in the Battle of Britain and the first bombing raids over Germany. New Zealanders who served in Lancasters were trained at the Lancaster Finishing School in England, and were then posted to combat units, including 75 Squadron – an RNZAF outfit “donated” to RAF Bomber Command for the war.

Of the more than 6000 Kiwi aircrew who served with Bomber Command during the Second World War – many in Lancasters – around one third were killed, injured or taken prisoner. This was a similar casualty rate to that in the trenches during World War I. Despite the high attrition rate, New Zealand aircrews rarely spoke out about dangerous or terrifying operations. There was a feeling that they were somehow better off than other Kiwis fighting on the ground in the deserts of North Africa or in Italy.

Two tours (60 ops in a Lancaster) were considered enough for survivors to be posted to HQ or Training Commands. Many veterans say that their time in Bomber Command, with fellows sharing a common goal and united by the sense of adventure and danger, were the best days of their lives.

Airmen suffering from shell shock or who just “lost the plot”, and who weren’t picked up by the station doctor and pulled off flying duties, weren’t so fortunate, and faced the horrific charge of Lack of Moral Fibre. They were not discharged, rather, stripped of rank, they were forced into menial service, still with their battle ribbons on as these were conferred by the King.