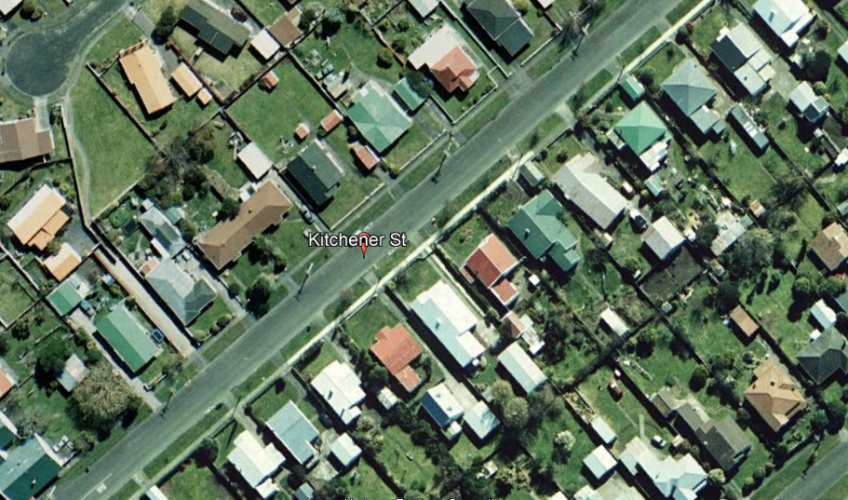

078 Kitchener Street Whanganui, street scene 2017

Reason for the name

It is believed that this street was named in honour of Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, PC, who was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator who won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his establishment of concentration camps during the Second Boer War, and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War. The full story about why Kitchener Street in Whanganui was so named has yet to be written.

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, PC (24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916), was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator who won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his establishment of concentration camps during the Second Boer War, and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War.

Kitchener was credited in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman and securing control of the Sudan for which he was made Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, becoming a qualifying peer and of mid-rank as an Earl. As Chief of Staff (1900–1902) in the Second Boer War he played a key role in Lord Roberts' conquest of the Boer Republics, then succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief – by which time Boer forces had taken to guerrilla fighting and British forces imprisoned Boer civilians in concentration camps. His term as Commander-in-Chief (1902–09) of the Army in India saw him quarrel with another eminent proconsul, the Viceroy Lord Curzon, who eventually resigned. Kitchener then returned to Egypt as British Agent and Consul-General (de facto administrator).

In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet Minister. One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and with the authority to act effectively on that perception, he organised the largest volunteer army that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight on the Western Front. Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 – one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government – and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

On 5 June 1916, Kitchener was making his way to Russia to attend negotiations, on HMS Hampshire, when it struck a German mine 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of the Orkney Islands, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

Author: Poppy Places Trust

Kitchener’s Story from WW1

At the outset of the First World War, the Prime Minister, Asquith, quickly had Lord Kitchener appointed Secretary of State for War; Asquith had been filling the job himself as a stopgap following the resignation of Colonel Seely over the Curragh Incident earlier in 1914. Kitchener was in Britain on his annual summer leave, between 23 June and 3 August 1914, and had boarded a cross-Channel steamer to commence his return trip to Cairo when he was recalled to London to meet with Asquith. War was declared at 11pm the next day.

Against cabinet opinion, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war that would last at least three years, require huge new armies to defeat Germany, and cause huge casualties before the end would come. Kitchener stated that the conflict would plumb the depths of manpower "to the last million". A massive recruitment campaign began, which soon featured a distinctive poster of Kitchener, taken from a magazine front cover. It may have encouraged large numbers of volunteers, and has proven to be one of the most enduring images of the war, having been copied and parodied many times since. Kitchener built up the "New Armies" as separate units because he distrusted the Territorials from what he had seen with the French Army in 1870. This may have been a mistaken judgement, as the British reservists of 1914 tended to be much younger and fitter than their French equivalents a generation earlier.

Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey wrote of Kitchener:

The great outstanding fact is that within eighteen months of the outbreak of the war, when he had found a people reliant on sea-power, and essentially non-military in their outlook, he had conceived and brought into being, completely equipped in every way, a national army capable of holding its own against the armies of the greatest military Power the world had ever seen.

However, Ian Hamilton later wrote of Kitchener "he hated organisations; he smashed organisations ... he was a Master of Expedients".

Deploying the BEF

At the War Council (5 August) Kitchener and Lt.-General Sir Douglas Haig argued that the BEF should be deployed at Amiens, where it could deliver a vigorous counterattack once the route of German advance was known. Kitchener argued that the deployment of the BEF in Belgium would result in having to retreat and abandon much of its supplies almost immediately, as the Belgian Army would be unable to hold its ground against the Germans; Kitchener was proved right, but given the belief in fortresses common at the time, it is not surprising that the War Council disagreed with him.

Kitchener, believing Britain should husband her resources for a long war, decided at Cabinet (6 August) that the initial BEF would consist of only 4 infantry divisions (and 1 cavalry), not the 5 or 6 promised.[76] His decision to hold back two of the six divisions of the BEF, although based on exaggerated concerns about German invasion of Britain, arguably saved the BEF from disaster as Sir John French (on the advice of Wilson who was much influenced by the French), might have been tempted to advance further into the teeth of the advancing German forces, had his own force been stronger.

Kitchener's wish to concentrate further back at Amiens may also have been influenced by a largely accurate map of German dispositions which was published by Repington in The Times on the morning of 12 August. Kitchener had a three-hour meeting (12 August) with Sir John French, Murray, Wilson and the French liaison officer Victor Huguet, before being overruled by the Prime Minister, who eventually agreed that the BEF should assemble at Maubeuge.

Sir John French’s orders from Kitchener were to cooperate with the French but not to take orders from them. Given that the tiny BEF (about 100,000 men, half of them serving regulars and half reservists) was Britain’s only field army, Lord Kitchener also instructed French to avoid undue losses and exposure to “forward movements where large numbers of French troops are not engaged” until Kitchener himself had had a chance to discuss the matter with the Cabinet.

Meeting with Sir John French

The BEF Commander Sir John French, concerned at heavy British losses at the Battle of Le Cateau, was considering withdrawing his forces from the Allied line. By 31 August Joffre, President Poincaré (relayed via Bertie, the British Ambassador) and Kitchener sent him messages urging him not to do so. Kitchener, authorised by a midnight meeting of whichever Cabinet Ministers could be found, left for France for a meeting with Sir John on 1 September.

They met, together with Viviani (French Prime Minister) and Millerand (now French War Minister). Huguet recorded that Kitchener was "calm, balanced, reflective" whilst Sir John was "sour, impetuous, with congested face, sullen and ill-tempered". On Bertie’s advice Kitchener dropped his intention of inspecting the BEF. French and Kitchener moved to a separate room, and no independent account of the meeting exists. After the meeting Kitchener telegraphed the Cabinet that the BEF would remain in the line, although taking care not to be outflanked, and told French to consider this "an instruction". French had a friendly exchange of letters with Joffre.

French had been particularly angry that Kitchener had arrived wearing his field marshal's uniform. This was how Kitchener normally dressed at the time (Hankey thought Kitchener’s uniform tactless, but it had probably not occurred to him to change), but French felt that Kitchener was implying that he was his military superior and not simply a cabinet member. By the end of the year French thought that Kitchener had "gone mad" and his hostility had become common knowledge at GHQ and GQG.

1915 Strategy

In January 1915, Field Marshal Sir John French, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, with the concurrence of other senior commanders (e.g. General Sir Douglas Haig), wanted the New Armies incorporated into existing divisions as battalions rather than sent out as entire divisions. French felt (wrongly) that the war would be over by the summer before the New Army divisions were deployed, as Germany had recently redeployed some divisions to the east, and took the step of appealing to the Prime Minister, Asquith, over Kitchener’s head, but Asquith refused to overrule Kitchener. This further damaged relations between French and Kitchener, who had travelled to France in September 1914 during the First Battle of the Marne to order French to resume his place in the Allied line.

Kitchener warned French in January 1915 that the Western Front was a siege line that could not be breached, in the context of Cabinet discussions about amphibious landings on the Baltic or North Sea Coast, or against Turkey.[83] In an effort to find a way to relieve pressure on the Western front, Lord Kitchener proposed an invasion of Alexandretta with Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), New Army, and Indian troops. Alexandretta was an area with a large Christian population and was the strategic centre of the Ottoman Empire's railway network — its capture would have cut the empire in two. Yet he was instead eventually persuaded to support Winston Churchill's disastrous Gallipoli Campaign in 1915–1916. That failure, combined with the Shell Crisis of 1915 – amidst press publicity engineered by Sir John French – dealt Kitchener's political reputation a heavy blow; Kitchener was popular with the public, so Asquith retained him in office in the new coalition government, but responsibility for munitions was moved to a new ministry headed by David Lloyd George. He was a sceptic about the tank, which is why it was developed under the auspices of Churchill’s Admiralty.

With the Russians being pushed back from Poland, Kitchener thought the transfer of German troops west and a possible invasion of Britain increasingly likely, and told the War Council (14 May) that he was not willing to send the New Armies overseas. He wired French (16 May 1915) that he would send no more reinforcements to France until he was clear the German line could be broken, but sent two divisions at the end of May to please Joffre, not because he thought a breakthrough possible.[85] He had wanted to conserve his New Armies to strike a knockout blow in 1916–17, but by the summer of 1915 realised that high casualties and a major commitment to France were inescapable. “Unfortunately we have to make war as we must, and not as we should like” as he told the Dardanelles Committee on 20 August 1915.

At an Anglo-French conference at Calais (6 July) Joffre and Kitchener, who was opposed to “too vigorous” offensives, reached a compromise on “local offensives on a vigorous scale”, and Kitchener agreed to deploy New Army divisions to France. An inter-Allied conference at Chantilly (7 July, including Russian, Belgian, Serb and Italian delegates) agreed on coordinated offensives. However, Kitchener now came to support the upcoming Loos offensive. He travelled to France for talks with Joffre and Millerand (16 August). The French leaders believed Russia might sue for peace (Warsaw had fallen on 4 August). Kitchener (19 August) ordered the Loos offensive to proceed, despite the attack being on ground not favoured by French or Haig (then commanding First Army).[88] The Official History later admitted that Kitchener hoped to be appointed Supreme Allied Commander. Liddell Hart speculated that this was why he allowed himself to be persuaded by Joffre. New Army divisions first saw action at Loos in September 1915.

Reduction in powers

Kitchener continued to lose favour with politicians and professional soldiers. He found it “repugnant and unnatural to have to discuss military secrets with a large number of gentlemen with whom he was but barely acquainted”. Esher complained that he would either lapse into “obstinacy and silence” or else mull aloud over various difficulties. Milner told Gwynne (18 August 1915) that he thought Kitchener a “slippery fish”. By autumn 1915, with Asquith’s Coalition close to breaking up over conscription, he was blamed for his opposition to that measure (which would eventually be introduced for single men in January 1916) and for the excessive influence which civilians like Churchill and Haldane had come to exert over strategy, allowing ad hoc campaigns to develop in Sinai, Mesopotamia and Salonika. Generals such as Sir William Robertson were critical of Kitchener's failure to ask the General Staff (whose chief James Wolfe-Murray was intimidated by Kitchener) to study the feasibility of any of these campaigns.

Kitchener advised the Dardanelles Committee (21 October) that Baghdad be seized for the sake of prestige then abandoned as logistically untenable. His advice was no longer accepted without question, but the British forces were eventually besieged and captured at Kut.

Archibald Murray (Chief of the Imperial General Staff) later recorded that Kitchener was “quite unfit for the position of secretary of state” and “impossible”, claiming that he never assembled the Army Council as a body, but instead gave them orders separately, and was usually exhausted by Friday. Kitchener was also keen to break up Territorial units whenever possible whilst ensuring that “No “K” Division left the country incomplete”. Murray wrote that “He seldom told the absolute the truth and the whole truth” and claimed that it was not until he left on a tour of inspection of Gallipoli and the Near East that Murray was able to inform the Cabinet that volunteering had fallen far below the level needed to maintain a BEF of 70 divisions, requiring the introduction of conscription. The Cabinet insisted on proper General Staff papers being presented in Kitchener’s absence.

Asquith, who told Robertson that Kitchener was “an impossible colleague” and “his veracity left much to be desired”, hoped that he could be persuaded to remain in the region as Commander-in-Chief and acted in charge of the War Office, but Kitchener took his seals of office with him so he could not be sacked in his absence. Douglas Haig – at that time involved in intrigues to have Robertson appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff – recommended that Kitchener be appointed Viceroy of India (“where trouble was brewing”) but not to the Middle East, where his strong personality would have led to that sideshow receiving too much attention and resources. Kitchener visited Rome and Athens, but Murray warned that he would likely demand the diversion of British troops to fight the Turks in the Sinai.

Kitchener and Asquith were agreed that Robertson should become CIGS, but Robertson refused to do this if Kitchener “continued to be his own CIGS”, although given Kitchener’s great prestige he did not want him to resign; he wanted the Secretary of State to be side-lined to an advisory role like the Prussian War Minister. Asquith asked them to negotiate an agreement, which they did over the exchange of several draft documents at the Hotel de Crillon in Paris. Kitchener agreed that Robertson alone should present strategic advice to the Cabinet, with Kitchener responsible for recruiting and supplying the Army, although he refused to agree that military orders should go out over Robertson’s signature alone – it was agreed that the Secretary of State should continue to sign orders jointly with the CIGS. The agreement was formalised in a Royal Order in Council in January 1916. Robertson was suspicious of efforts in the Balkans and Near East, and was instead committed to major British offensives against Germany on the Western Front — the first of these was to be the Somme in 1916.

1916

Early in 1916 Kitchener visited Douglas Haig, newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the BEF in France. Kitchener had been a key figure in the removal of Haig's predecessor Sir John French, with whom he had a poor relationship. Haig differed with Kitchener over the importance of Mediterranean efforts and wanted to see a strong General Staff in London, but nonetheless valued Kitchener as a military voice against the folly of civilians such as Churchill. However, he thought Kitchener "pinched, tired, and much aged", and thought it sad that his mind was “losing its comprehension” as the time for decisive victory on the Western Front (as Haig and Robertson saw it) approached. Kitchener was somewhat doubtful of Haig's plan to win decisive victory in 1916, and would have preferred smaller and purely attritional attacks, but sided with Robertson in telling the Cabinet that the planned Anglo-French offensive on the Somme should go ahead.

Kitchener was under pressure from French Prime Minister Aristide Briand (29 March 1916) for the British to attack on the Western Front to help relieve the pressure of the German attack at Verdun. The French refused to bring troops home from Salonika, which Kitchener thought a play for the increase of French power in the Mediterranean.

On 2 June 1916, Lord Kitchener personally answered questions asked by politicians about his running of the war effort; at the start of hostilities Kitchener had ordered two million rifles from various US arms manufacturers. Only 480 of these rifles had arrived in the UK by 4 June 1916. The numbers of shells supplied were no less paltry. Kitchener explained the efforts he had made to secure alternative supplies. He received a resounding vote of thanks from the 200 Members of Parliament who had arrived to question him, both for his candour and for his efforts to keep the troops armed; Sir Ivor Herbert, who, a week before, had introduced the failed vote of censure in the House of Commons against Kitchener's running of the War Department, personally seconded the motion.

In addition to his military work, Lord Kitchener contributed to efforts on the home front. The knitted sock patterns of the day used a seam up the toe that could rub uncomfortably against the toes. Kitchener encouraged British and American women to knit for the war effort, and contributed a sock pattern featuring a new technique for a seamless join of the toe, still known as the Kitchener stitch.

Russian mission

In the midst of his other political and military concerns, Kitchener had devoted personal attention to the deteriorating situation on the Eastern Front. This included the provision of extensive stocks of war material for the Russian armies, which had been under increasing pressure since mid-1915. In May 1916 the Chancellor of the Exchequer Reginald Mckenna suggested that Kitchener head a special and confidential mission to Russia to discuss munition shortages, military strategy and financial difficulties with the Imperial Russian Government and the Stavka (military high command), which was now under the personal command of Tsar Nicholas II. Both Kitchener and the Russians were in favor of face to face talks and a formal invitation from the Tsar was received on 14 May. Kitchener with a party of officials, military aides and personal servants left London by train for Scotland on the evening of 4 June.

Death

Lord Kitchener sailed from Scrabster to Scapa Flow on 5 June 1916 aboard HMS Oak before transferring to the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire for his diplomatic mission to Russia. Shortly before 19:30 hrs the same day, steaming towards the Russian port of Arkhangelsk during a Force 9 gale, Hampshire struck a mine laid by the newly launched German U-boat U-75 and sank west of the Orkney Islands. Recent research has set the death toll of those aboard Hampshire at 737. Only twelve survived. Amongst the dead were all ten members of his entourage. Kitchener was seen standing on the quarterdeck during the approximately twenty minutes that it took the ship to sink. His body was never recovered.