052 Kitchener Street Hastings, street view

Reason for the name

The street was named in honour of Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener of Khartoum and of Broome

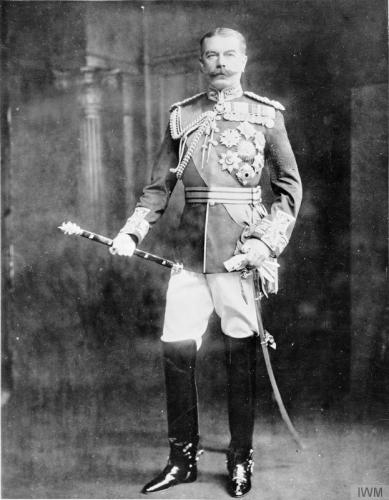

The street was named after Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener of Khartoum and of Broome - also known as Viscount Broome of Broome, Baron Denton of Denton, also called Baron Kitchener of Khartoum and of Aspall (from 1898) and Viscount Kitchener of Khartoum, of the Vaal, and of Aspall (from 1902). He was born June 24, 1850, near Listowel, County Kerry, Ireland and died June 5, 1916, at sea off Orkney Islands.

Kitchener had a varied, highly successful career. He served / worked in Palestine, Cyprus, Egypt and Zanzibar. He surveyed the River Nile (1884), fought at the Battle of Toski (1889), reorganised the Egyptian Police Force (1890/91). In 1896, Kitchener was a Major General and in 1898 he fought in the Battle of Omdurman. In the following year Kitchener was appointed Governor General of Sudan with the rank of Lieutenant General.

Kitchener fought in the Boer Wars where he held the rank of Commander-in-Chief South Africa as a full general. Between 1902 and 1909, he was Commander-in-Chief, India. In 1909, Kitchener was promoted to Field Marshal. As war clouds in Europe gathered in 1914, it was only natural that he was approached to join the Cabinet. He was Secretary of State for War when World War One was declared on August 4th 1914.

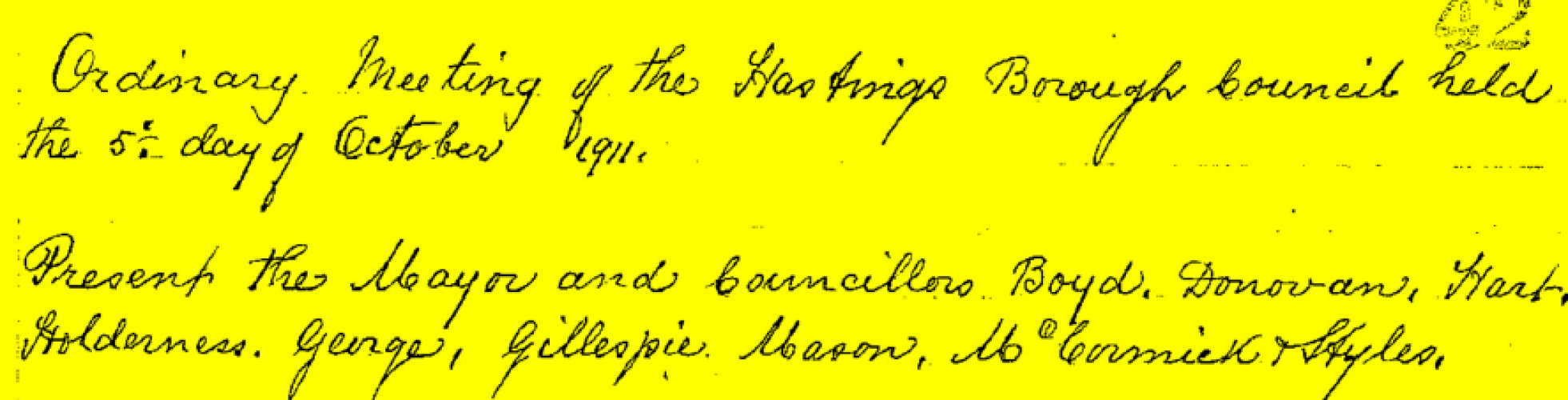

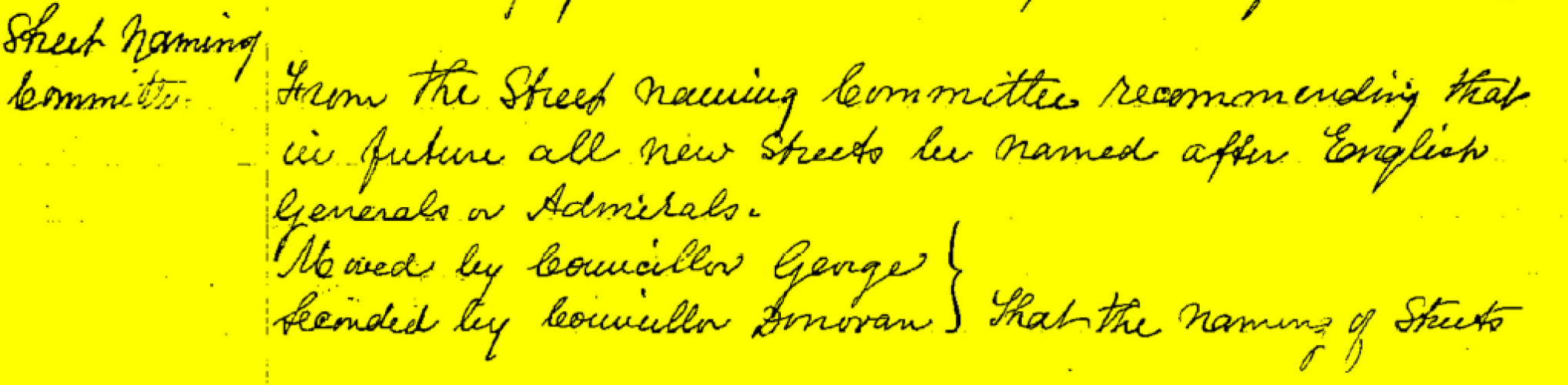

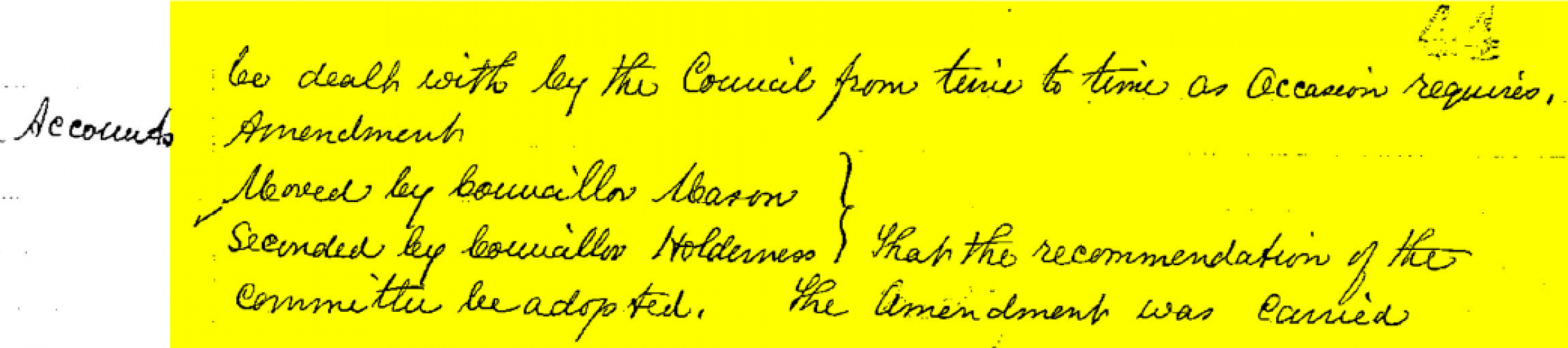

Hastings Borough Council at the time was naming many new streets for English Generals and Admirals, and even created a policy to do so for a time in 1911.

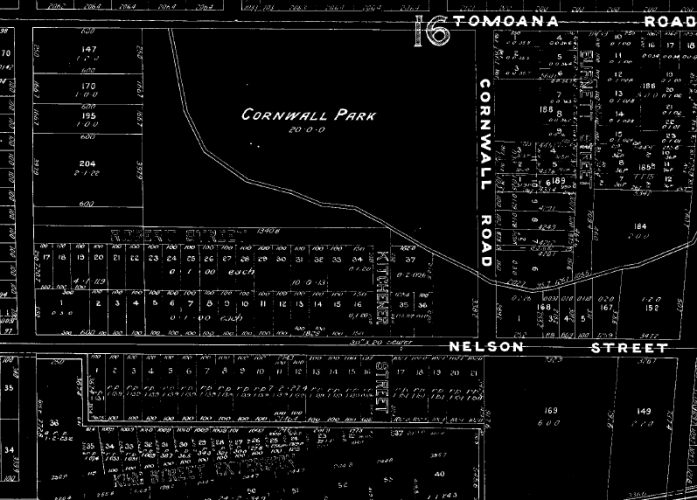

Kitchener Street is located near Cornwall Park in Hastings. It adjoins Roberts Street.

Authors: Cherie Flintoff, Helen Gelletly, Katrina Barrett

Lord Kitchener was an Irish-born senior British Army officer who won fame for his imperial campaigns and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War, although he died halfway through it.

Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank, Field Marshal, on 10 September 1909 and went on a tour of Australia and New Zealand. Through his career, he set the most meticulous of standards and impressed his senior officers.

Sir Evelyn Baring, the de facto British ruler of Egypt, thought Kitchener “the most able (soldier) I have come across in my time. At 6ft 2in, with piercing blue eyes, he was an imposing presence, bearing in mind that at the time he towered over most of his contemporaries.

In addition to his military prowess, he contributed to the soldiers’ comfort by encouraging British and American women to knit for the war effort, using a sock pattern with a new seamless join of the toe, still known as the Kitchener stitch, doing away with the usual seam that rubbed uncomfortably against the toes.

Kitchener won fame in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman and securing control of the Sudan, after which he was given the title "Baron Kitchener of Khartoum and of Aspall (in Suffolk)". Kitchener had ensured his men were well-armed with modern weapons and well trained. The battle was brutal, with artillery and machine guns able to massacre poorly armed Mahdist forces. This is likely to have reinforced to Kitchener the futility of full scale troop charges against modern weaponry.

Kitchener became Governor-General of the Sudan in September 1898 and began a programme of restoring good governance to the Sudan. The programme was based on education and children from any social class could apply to study. He ordered the mosques of Khartoum rebuilt, instituted reforms which recognised Friday — the Muslim holy day — as the official day of rest, and guaranteed freedom of religion to all citizens of the Sudan.

As Chief of Staff (1900–02) in the Second Boer War he played a key role in Lord Roberts' conquest of the Boer Republics, then succeeded Roberts as Commander-in-Chief. The first New Zealand contingent arrived in South Africa in December 1989. An additional two full battalions of Mounted Rifles, known as the 4th and 5th New Zealand Contingents, were sent to South Africa at the end of March 1990, and disembarked at Beira at the end of April. The two New Zealand contingents took part in the attempt to relieve Colonel Hore at Elands River.

In Lord Roberts' telegram of 18th August he spoke of an engagement at Buffelshoek, in which Carrington and Lord Erroll drove back the enemy in the vicinity of Elands River on 16th August, the day on which Hore was relieved by Lord Kitchener from the south. Lord Roberts remarked, "The New Zealanders particularly distinguished themselves. Our casualties: killed, New Zealand MI, Captain Harvey and 2 men; wounded, 9 men".

Twenty-eight New Zealand Nurses were known to have served in the Boer war. Two of these received special mention: Janet Williamson: Royal Red Cross (RRC), 27 September 1901; Mentioned in Dispatches - Lord Roberts, 4 Sept 1901; and Dora Peiper: Mentioned in Despatches - Lord Kitchener, 23 June 1902.

Along with the post, Kitchener inherited the (controversial) strategies of concentration camps and burning farms, designed by Roberts to force the commando Boer forces to surrender.

New Zealand Premier Richard Seddon visited South Africa in 1902 at Lord Kitchener's invitation. Peace negotiations were in process when he arrived. Kitchener helped moderate in the negotiation of peace in 1902 to ensure a settlement both the Boers and British could live with.

In 1902, he was created Viscount Kitchener of Khartoum and of the Vaal and of Aspall. As Commander in Chief in India until 1909, he reorganised their armed forces to prepare them for fighting an external war, not just internal rebellion.

In early 1910, Lord Herbert Kitchener was invited by the New Zealand government to visit and advise on the country's defence arrangements. At the conclusion of his visit he made a number of recommendations, one of which was the establishment of a New Zealand Staff Corps. At around the same time he stated that the Cadet movement had an important role to play in the Defence of the Empire. Subsequently, the Army began to provide uniforms, rifles and other equipment to the units. This Army support continued through World War One, with many ex-school cadets making up the officers and non-commissioned officers of the First Expeditionary Force. He also recommended a Territorial Force (to replace an ineffective Volunteer Force), and an extension of compulsory military training. The New Zealand Army Nursing Service commenced in 1912, following Lord Kitchener's visit. It appears that the Nursing Service and Army Medical Service were discussed during his visit.

Lord Kitchener had some connections to New Zealand prior to his visit in 1910; his father had bought a South Island sheep station in the 1860's, and had at various times resided on it, and his older brother had also managed the property.

He had strong-minded relatives in New Zealand, with a niece Frances Parker born in Kurow, Otago who became a campaigner for women’s rights in England after she left New Zealand in 1896 to study at Cambridge, paid for by her Uncle, Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener.

In 1911 he became Consul-General in Egypt, until August 1914. His key interests were in protecting the peasants from seizure of their land for debt and the advancement of cotton-growing.

In June 1914 Kitchener was made an Earl, with an additional viscountcy and barony, and shortly thereafter at the start of the First World War, Lord Kitchener became a Cabinet Minister and Secretary of State for War. The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, was pleased that Britain’s most eminent soldier had joined his Cabinet.

Kitchener did not believe the general public and political view that the war would be over by Christmas 1914. He informed the Cabinet of his views that World War One would last between three and four years and that the UK would have to mobilise millions of men if the war was to be won. It was a remarkably accurate prophecy. Kitchener's presence created a hold over his contemporaries. His close friend, Raymond "Conk" Marker, mixed affection with awe:

"In this age of self-advertisement there was always a danger that Lord K. with his absolute contempt for anything of the kind… would not be appreciated at his real value, but I think the country recognises him now.

The more I see of him the more devoted I get to him. He is always the same - never irritable - in spite of all his trials, and always making the best of things however much he may be interfered with. As Chamberlain said, to praise him is almost an impertinence."

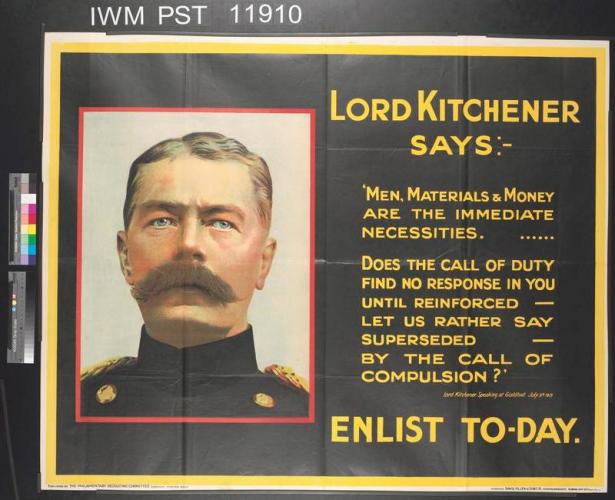

He organised the largest volunteer army that both Britain and the world had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight Germany on the Western Front.

His commanding image, appearing on recruiting posters demanding "Your country needs you!" remains recognised and parodied in popular culture. Without his appeal for volunteers, Britain could not have survived the early stages of the fighting.

Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning Britain for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 – one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government – and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

He had until then been in charge of national recruiting, overseeing the management of the UK’s industries and being responsible for military strategy. It was a huge workload for a man who had no great desire to delegate, when the most competent officers had gone to France with the British Expeditionary Force.

While he had significant influence, even as Secretary of War Kitchener was often overruled, to the detriment of the war effort.

In the early deployment of the British Expeditionary Force he wanted to concentrate further back at Amiens. This may have been influenced by a largely accurate map of German dispositions published by Repington in The Times on the morning of 12 August. Kitchener had a three-hour meeting that day with Sir John French, Murray, Wilson and the French liaison officer Victor Huguet, before being overruled by the Prime Minister, who eventually agreed that the BEF should assemble at Maubeuge.

With the Western Front quickly settling into trench warfare in 1915, Lord Kitchener proposed an invasion of Alexandretta with Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), New Army, and Indian troops. Alexandretta was an area with a large Christian population and was the strategic centre of the Ottoman Empire's railway network — its capture would have cut the empire in two. Rebuffed, he was talked into supporting Winston Churchill's attack on Gallipoli.

In WWI, between 12th and 15th November 1915, he visited Gallipoli as Britain's Secretary of State for War to inspect the Allies' positions. Although Field Marshall Lord Kitchener had initially opposed withdrawal from Gallipoli, the exhausted state of Allied soldiers, the prospect of a harsh winter and the growing strength of the Ottomans forced him to reconsider. Following his visit, on 22 November Kitchener cabled London to recommend the evacuation from positions at Anzac and Suvla.

The visit of Lord Kitchener of Khartoum to the Anzac battlefields started troops speculating. His visit, needless to say, was very secret. On landing he went straight to Russell's Top and right through the trenches on the Nek. Indians passed by the way were overawed and simply went down on their knees. Needless to say there were wonderful rumours as to what he did and said, but it was generally understood that the decision to evacuate the Peninsula was confirmed there and then. Viewing the country from the observing station of the 2nd Battery, N.Z.F.A., he was much impressed by the rough country.

The Gallipoli campaign was difficult from the start, with the terrain and conditions. Key beachheads that were secured were overlooked by Turkish forces. In November 1915, upon seeing conditions for himself, Kitchener supported an immediate evacuation.

Opponents, including Douglas Haig, intrigued to have Robertson appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff in January 1916, lessening Kitchener’s power.

Kitchener was blamed for the thousands of lives had been lost in the doomed Gallipoli adventure, which was not of his making, and for the British industries’ inability to supply as many artillery shells as the fighting demanded in the spring of 1915. However, he was given a resounding vote of thanks from Parliament after answering questions in June 1916 about efforts to obtain other arms, including two million rifles ordered from various US arms manufacturers at the start of hostilities, only 480 of which had arrived.

He had seen in the Boer War the use of mobile tactics, machine guns, defensive positions and modern weapons.

Haig reportedly thought Kitchener was tired and losing his edge, as Haig and Robertson were sure the time was right for a decisive victory on the Western Front, while Kitchener was doubtful and would have preferred smaller and purely attritional attacks. Despite his misgivings, and possibly partly due to his reduced influence by this time, Kitchener supported Robertson and Haig’s planned Anglo-French offensive on the Somme in Cabinet. The Battle of the Somme began after Kitchener’s death, and is famous for the loss of 58,000 British troops (one third of them killed) on the first day of the battle, 1 July 1916, which to this day remains a one-day record. The British had poor quality artillery shells and many didn’t explode, but troops were told to expect an easy advance after the 8-day barrage. They made easy targets for the German machine-gunners, as perhaps Kitchener had feared.

Kitchener eventually resigned his Cabinet position, but was still involved in supporting war efforts. Kitchener drowned on 5 June 1916 when HMS Hampshire sank west of the Orkney Islands, Scotland. He was making his way to Russia to discuss military matters when the ship suffered an explosion, presumed to have been from hitting a German mine, in a storm. He was one of more than 600 killed on board the ship.

A Kitchener Scholarship was set up in 1916 for sons of New Zealanders who lost their lives in the Great War, and broadened to wider military / other recipients in 1941, through the Kitchener Memorial Scholarship Trust Act 1941.

A highly religious man, Kitchener once stated his own attitude: “Not to work to one’s full, is to defraud God.”