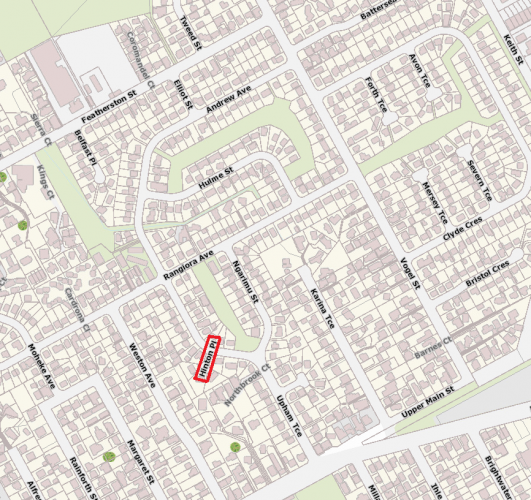

115 Hinton Pl Palmerston North, as viewed from Upham Terrace 2017

Reason for the name

This street was named in honour of Sergeant John Daniel Hinton VC.

The suburb now known as Roslyn was originally part of the suburb of Terrace End. One of the early residents of Terrace End was Mr Charles Ross, a draper, who built a large house in the area. After his death in 1924, his widow sold 20 acres of land to the Government, who promptly named the area Roslyn in honour of him. Following the initial state house development of Rangiora Avenue on this land, further sections to the east of the area were sought for redevelopment. This included sections 173 to 179, owned by J D Buchanan, another prominent Palmerston North local, and this land was purchased by the Department of Housing in November 1944.

A motion at a Council Meeting on 19 August 1946 created a sub-committee for street naming made up of the Mayor, as well as Councillors Hart and Tremaine. On 17 March 1947 this committee recommended that those roads making up the old Buchanan and Main Street blocks were to be named after suggested Victoria Cross recipients. Although the Palmerston North Branch of the Returned Services Association suggested “VC” be added to each street, this was not adopted.

Hinton Street is a cul-de-sac which is approximately 30 metres long and is home to 6 residential houses. Its only entrance is via the Rangiora Avenue end of Upham Terrace. To the east lies Rangiora Reserve, with other amenities in the area including Memorial Park, Vogel Street & Main Street parks, and Roslyn Kindergarten.

Author: Evan Greensides, Heritage Assistant for Palmerston North City Libraries & Community Services.

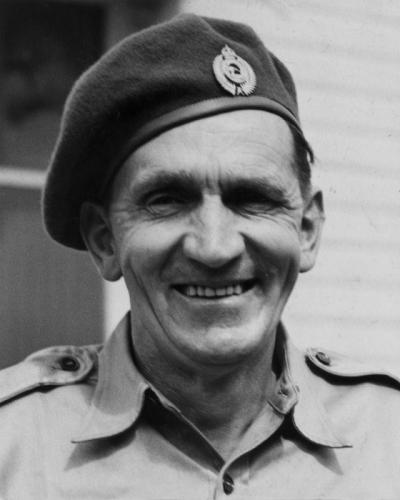

About Sergeant John Daniel Hinton

John Daniel Hinton, also known as “Jack”, was born in Colac Bay, Southland, on 17 September 1909, being the fifth child of Harry Godfrey Hinton, a New Zealand Railways employee, and Mary Elizabeth Hinton . At the age of five, Jack began his education at Colac Bay School, which went up to Standard 6. Around this time, Jack started his first job of many – milking cows at Harrison’s, a local farm. At the age of twelve he ran away from home, heading to nearby Tokanui where he became a deliveryman for a local grocer. As the Depression hit New Zealand in the early 1930s and work became hard to come by, Jack took any job he could find: first, farming in the Otago high-country on various farms, then helping to build the railway to Westport, a stint on a large Norwegian whaling ship, prospecting for gold, working at a sawmill in Lyell, and then as a horse trainer. Finally, after meeting Eunice Henriksen, he became a publican when he went in on the lease with her for the Hari Hari Hotel in Westland in 1937, also working at that time for the Ministry of Works.

When war broke out in 1939 he was one of the first to enlist in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Afraid that the war would be over before they arrived in Europe, Jack and 20 friends travelled to Greymouth to enlist. With his previous management skills and maturity, Jack quickly distinguished himself as a natural leader among men during the months of basic training at Burnham, earning the affinity of men under his command and being rapidly promoted to the rank sergeant. Fellow soldier, Frank Helm, would later comment, “Although Jack was 10 years older than the rest of us, he was always one of us. Even when he was a sergeant, he was still one of the boys.” Jack left New Zealand in January 1940 as part of the 20th Battalion

As part of the 2nd New Zealand Division, Jack soon found himself in Greece as part of Lustre Force. Initially defending the Katerini region along the Aliakmon Line, the division was soon forced to retreat after the German invasion on 6 April 1941. During this action, Jack was attached to a group of soldiers who were to stay in reserve and provide reinforcements for the division if needed, being sent to the port of Kalamata. By the 14 April the reality of the situation became clear to Allied forces, whereupon the 2nd New Zealand Division was ordered to evacuate Greece.

With around 6000 troops due to leave Kalamata via Royal Navy destroyers on 27 April there was much disorganisation in the town, with German forces not far away. Advanced units of 5 Panzer Division broke through the thinly guarded frontline the next day and reached the quay where evacuations were taking place. The scene was chaotic; there was no overall command, firefights erupted at multiple points throughout the town, and the naval liaison officer communicating with the evacuating ships was captured.

Jumping immediately into action, Jack went forward to battalion headquarters to ascertain the situation. Hearing Brigadier Parrington order the men around him to surrender, Jack replied, “Surrender? Go and jump in the bloody lake!”. Setting off, he collected 12 other New Zealand soldiers and led them into town, advancing on a 6 inch gun after wiping out a machine gun crew in his way. When the gun crew noticed Jack advancing they fired point-blank and missed. Jack, hurling grenades, was supported by machine-gun fire and the soldiers he was leading, forcing the gun crew and another nearby crew to abandon their positions and seek shelter in nearby houses. Jack soon followed up his attack with the others in a bayonet charge, wiping out both crews. At the end of the assault, a single German soldier fleeing the New Zealand troops fired at Jack with a submachine gun, wounding him in the stomach.

Although the town had been recaptured and control of the quay restored, Royal Navy destroyers witnessing the action offshore assumed that the town had been lost, as the naval liaison officer, who had been captured, was not able to say otherwise. With no ships coming in shore to evacuate them, the troops left behind surrendered in the early hours of the morning to advancing German tanks and infantry. Immobilised by his wounds and with little time to escape, Jack soon became a POW, along with thousands of others.

Soon after the action, in letters home from hospitals and POW camps, New Zealand soldiers told of Jack’s courageous actions during the fighting at Kalamata. An immediate investigation took place, and on 14 October 1941 the London Gazette announced the award of the Victoria Cross to Jack. Medals are not normally conferred on soldiers while they are prisoners of war, therefore it was a major break with precedent when the announcement of the award of the Victoria Cross to was made. Jack, then at Stalag IX-C near Bad Sulza, only learnt of this when he was hauled out of solitary confinement, still recovering from a beating after one of several unsuccessful escape attempts, and presented with a makeshift crimson ribbon in place of the medal by the commandant of the camp. As a report on his conduct as POW later stated,

Sgt Hinton in Stalag 9C kept the boys in a good state of morale, made himself unpopular with the Germans as a result of constant consideration for the men, especially New Zealanders. Sgt Hinton also made one escape but unfortunately through a railway accident he was recaptured before being able to leave the country.

After being liberated by American troops in April 1945, Jack borrowed a uniform and fought alongside US troops before his nationality was discovered and he was repatriated to the UK. Jack was finally presented with his Victoria Cross during an investiture at Buckingham Palace by King George VI in May 1945. After returning to New Zealand, Jack started his civilian life as a publican, managing and owning numerous pubs in various New Zealand towns. As with fellow Victoria Cross recipient Charles Upham, Jack was always reticent about the distinction, once stating, “Congratulate them, not me. I had my war cut short. My mates went on to fight more battles. They are the real heroes.” Jack married twice and, after living out his retirement in Christchurch, died in 1997 at the age of 87. Being New Zealand’s last surviving Victoria Cross holder, over 800 people attended the funeral, including a 100-strong honour guard and Chief of Staff, Major General Piers Reid. Jack Hinton is buried in the returned services section at the Ruru Lawn Cemetery, Christchurch; his medals are currently on loan from the Hinton family to the National Army Museum in Waiouru until 2028.

Honours and Awards

- Victoria Cross

- 1939-1945 Star

- Africa Star

- Defence Medal

- War Medal 1939-1945 with bronze oak leaf cluster

- New Zealand War Service Medal

- Coronation Medal 1953

- Silver Jubilee Medal 1977

- New Zealand 1990 Commemoration Medal

Citation for Victoria Cross, London Gazette, 14 October 1941:

On the night of 28-29 April 1941, during the fighting in Greece, a column of German armoured forces entered Kalamai; this column, which contained several armoured cars, 2 inch guns and 3 inch mortars and two 6 inch guns, rapidly converged on a large force of British and New Zealand troops awaiting embarkation on the beach. When the order to retreat to cover was given, Sergeant Hinton, shouting ‘To hell with this, who’ll come with me?’, ran to within several yards of the nearest gun; the gun fired, missing him, and he hurled two grenades, which completely wiped out the crew. He then came on with the bayonet, followed by a crowd of New Zealanders. German troops abandoned the first 6 inch gun and retreated into two houses. Sergeant Hinton smashed the window and then the door of the first house, and dealt with the garrison with the bayonet. He repeated the performance in the second house, and as a result, until overwhelming German forces arrived, the New Zealanders held the guns. Sergeant Hinton then fell with a bullet wound through the lower abdomen and was taken prisoner.