043 Haig Street, Hastings, street view

Reason for the name

Field Marshall Douglas Haig was one of the key leaders of the British and Commonwealth forces in World War I (WWI). He was Commander in Chief from December 1915 until the end of the war.

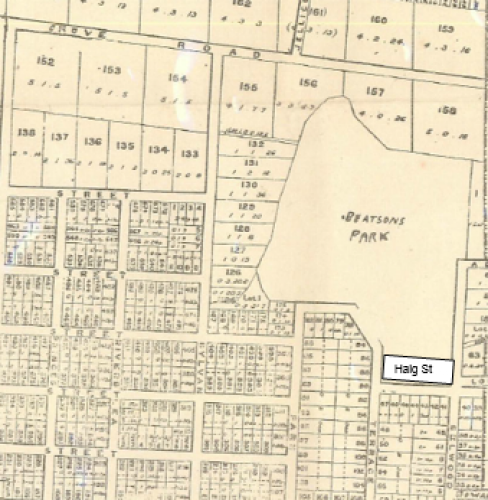

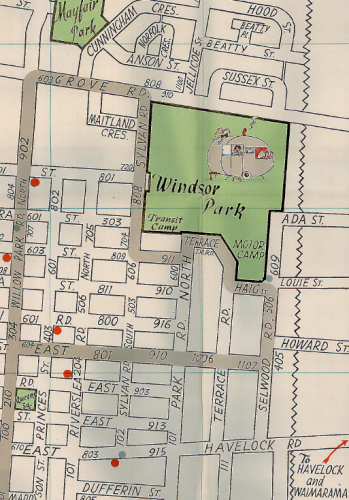

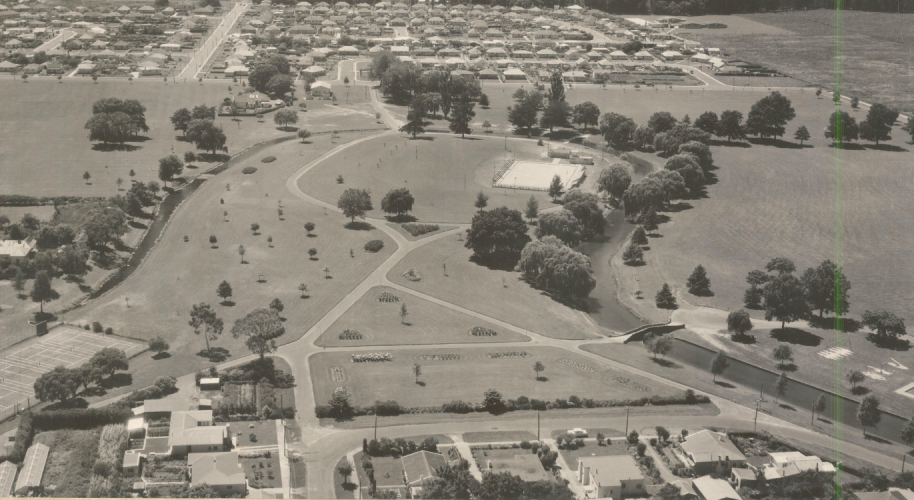

Haig Street is located beside Windsor Park in Parkvale (shown as Beatsons Park in an advertising map ca. 1925). It was once part of Park Terrace or Terrace Lane.

Napier Hastings City Map, ISBN 978-1-877-4547-21-0 Coordinates E4

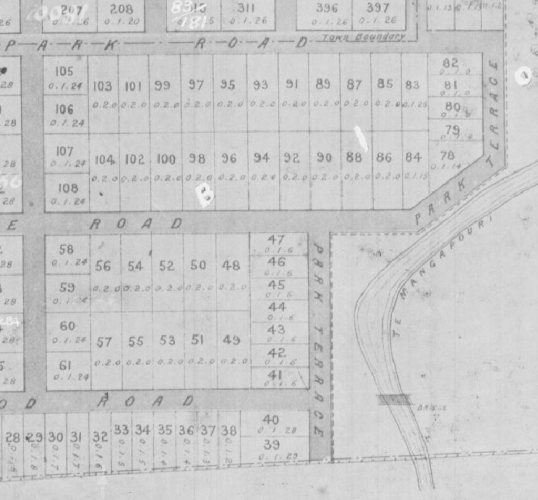

In the Gallery is a map from 1892 showing Haig Street used to be part of Park Terrace – the angled part of Park Terrace became part of Terrace Road and the straight part adjoining the park (now Windsor Park with attractions like Splash Planet, and at the Haig St end Hastings Holiday Park) from property numbers 39-47 became Haig Street. Note this map does not use the North orientation of the current-day map and shows Te Mangapouri stream that is now the Windsor Park “pond”.

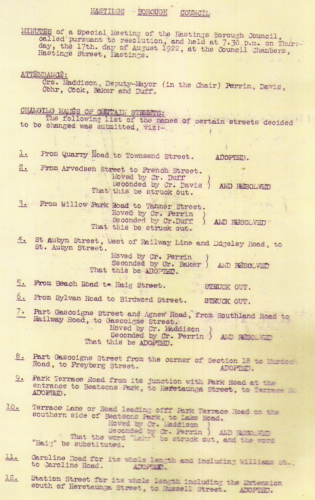

Haig Street was (re)named at a Council meeting on 17 August 1922. See the gallery for verification

Author: Cherie Flintoff

After the end of WW1 Field Marshall the Earl Haig set up the Haig Fund to help all servicemen who were either financially hard up or were incapacitated due to being wounded, becoming the Poppy appeal in time.

1st Earl and Field Marshall Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE, ADC

Field Marshal Douglas Haig (19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a British senior officer during the First World War. He commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from 1915 to the end of the war. He was commander during the Battle of the Somme, the battle with one of the highest casualties in British military history, the Third Battle of Ypres and the Hundred Days Offensive, which led to the armistice in 1918.

Haig saw overseas service in India from 1886-1892 and was made up to Captain. In 1893 he failed to gain entrance to Camberley Staff College and returned briefly to India before he was finally nominated for the Staff College in late 1894. While waiting to take up his place, he travelled to Germany to report on cavalry manoeuvres there, and also served as staff officer to Colonel John French. The careers of French and Haig were to be entwined for the next twenty-five years, until Haig voiced his disquiet about French during battles in France in 1915 and eventually replaced him as Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force.

During the Boer War Haig earned promotions, and became a Major-General. His tactics in the war followed the standard (at the time) British scorched earth policy of burning farms and putting Boer women and children in concentration camps.

Haig had called for larger Army Reserves and helped set up the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1907. He reluctantly, as he foresaw a likely war in Europe, returned to India in 1909 for a couple of years and was promoted to Lieutenant-General in 1910.

When WWI began in August 1914, Haig helped organize the BEF, commanded by Field Marshal Sir John French. He was critical both of Field Marshal French and of the French (France’s) forces. Haig was in a leading command role for the whole of WWI, becoming Commander in Chief in December 1915 on the ouster of Field Marshall French.

Haig saw himself as God's servant and was keen to have clergymen sent out whose sermons would remind the men that the war dead were martyrs in a just cause.

After retiring from the service, Haig devoted the rest of his life to the welfare of ex-servicemen. Haig pushed for one organisation for their welfare, The Royal British Legion, which was founded in June 1921, and opposed having a separate organisation for officers. He was also instrumental in setting up the Haig Fund for the financial assistance of ex-servicemen and the Haig Homes charity to ensure they were properly housed. He promoted ex-servicemen’s rights in Commonwealth countries too. Haig’s leadership has been both criticised and defended in more recent times.

Some revisionist historians have criticised Haig for issuing orders which led to excessive casualties of British troops under his command on the Western Front. Part of this was the nature of war and particularly trench warfare, which is a brutal activity with high casualties. Note that “casualties” refers to the injured as well as those killed.

Military History magazine in 2007 called him, "World War I's Worst General." Called (after the fact, not at the time) "Butcher Haig" for the two million British casualties under his command, he was blamed for lack of use of modern tactics and technology. The Canadian War Museum comments, "His epic but costly offensives at the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917) have become nearly synonymous with the carnage and futility of First World War battles."

The rains finally brought the Somme offensive to an end. Soldiers had to contend with mud, artillery fire, gas attacks, grenades, bullets and bayonets. They also had to be ready to dig trenches, pull equipment out of the mud, run communication wires, and charge through barbed wire and enemy fire.

Haig is said by some more modern historians to have taken quite an old fashioned approach to war, focusing on gaining ground, with high attrition on both sides. However, he was also working with the equipment available for use (in 1915 the Germans had 10,500 guns of which 3,350 were heavy, whilst the British had only around 1,500, and a shortage of ammunition). Some of the battles fought were planned to tie up German forces to relieve the pressure on French lines, and not all were timed or designed as Haig wanted, and this is subtly reflected in his Despatches. Haig did understand the need to consider the flanks and not just focus on a frontal attack. He had a strong emphasis on the role of cavalry, was reputed not to think highly of artillery. However, reading his Despatches on the Battle of the Somme, Haig did use artillery prior to deploying the troops.

He was a man of his time, working with the British forces, systems (including class and appointment systems) and equipment available. Reports show he tried to ensure troops were trained and ready before engaging. After the war Haig was praised by the American General John Pershing, who remarked that Haig was "the man who won the war". He was also publicly lauded as the leader of a victorious army.

Since the 1980s other historians have argued that the negative view of Haig that had developed failed to recognise the adoption of new tactics and technologies by forces under his command, the important role played by British forces in the Allied victory of 1918 and that high casualties were a consequence of the tactical and strategic realities of the time.

Douglas Haig died in London from a heart attack, aged 66, on 29 January 1928 and was given an elaborate funeral on 3 February. Huge crowds lined the streets. Three royal princes followed the gun-carriage and the pall-bearers included two Marshals of France (Foch and Pétain).