014 French Street, Hamilton, street scene 2018

Reason for the name

This street was named in honour of WW1 Field Marshall Sir John Denton Pinkstone French 1852-1925, Earl of Ypres.

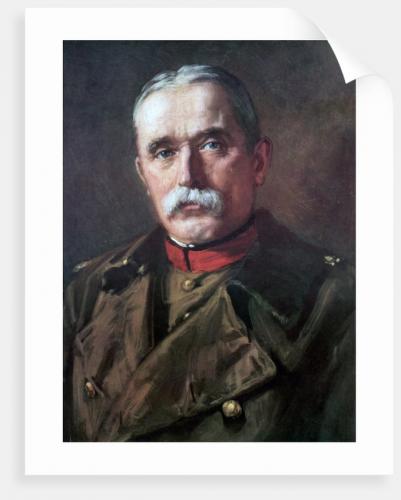

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC, known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer.

The Hamilton streets of French, Joffre, Haig and Beattie were all named after British WW1 Admirals and Generals which was a common practice of street naming in that post-war era.

Author: Poppy Places Trust

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC,

known as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a British Army officer.

Born in Ripple, Kent on September 28, 1852 to an Anglo-Irish family, he saw brief service as a midshipman in the Royal Navy, before becoming a cavalry officer. He achieved rapid promotion and distinguished himself on the Gordon Relief Expedition. French was reportedly a notorious womaniser throughout his life and poorly managed money, needing to be financially bailed out on several occasions by his brother-in-law and once by (his then trusted subordinate) Douglas Haig.

French became a national hero during the Second Boer War. He won the Battle of Elandslaagte near Ladysmith, escaping under fire on the last train as the siege began. He then commanded the Cavalry Division, winning the Battle of Klip Drift during a march to relieve Kimberley. He later conducted Counter-insurgency operations in Cape Colony.

French became Chief of the Imperial General Staff (professional head of the Army) in 1912. During this time he helped to prepare the BEF for a possible European War, and was also one of those who insisted, in the so-called “cavalry controversy”, that cavalry still be trained to charge with cold steel rather than just fighting dismounted with firearms. During the Curragh incident he had to resign as CIGS after promising Hubert Gough in writing that the Army would not be used to coerce Ulster Protestants into a Home Rule Ireland.

French’s most important role was as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force for the first year and a half of World War I. While he is reported to have clashed with the French Army’s General Lanrezac, his despatches reflect a friendly relationship with General Joffre.

After the British suffered heavy casualties at the battles of Mons and Le Cateau (where by some reports Smith-Dorrien made a stand contrary to his wishes, though in his Despatches of this time French mentions the valuable services of Smith-Dorrien as a “commander of rare and unusual coolness, intrepidity, and determination”), French wanted to withdraw the BEF from the Allied line to refit. Despatches about Marne note “from Sunday, August 23rd, up to the present date (September 17th), from Mons back almost to the Seine, and from the Seine to the Aisne, the Army under my command has been ceaselessly engaged without one single day's halt or rest of any kind.” He agreed to take part in the First Battle of the Marne after a private meeting with the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener.

Later, in May 1915, French, frustrated by a lack of supplies, leaked information about shell shortages to the press. By summer 1915 French was being increasingly criticised in London by Kitchener and other members of the government, and by Haig, Robertson, and other senior generals in France. French and others had tried to delay engaging on the Western Front until 1916, when they could have more men and munitions available, but pressure from their ally France and concerns about the Russian / Eastern Front led to them committing to a battle they weren’t ready for, on ground they didn’t think suitable against German forces that had spent months preparing their fortifications.

During the Battle of Loos, French’s allegedly slow release of XI Corps from reserve was blamed for the failure to achieve a decisive breakthrough on the first day. There are mixed views on whether the delay in the troops arriving was French’s fault, as the troops were fresh and tired from marching and were delayed by poor road conditions and other obstacles. This was compounded by a shift of some of the GHQ staff including French to an area reliant only on the public telephone system for communication. The artillery was relatively light and bombardments not as successful as hoped, particularly with the Germans second lines of defence, and the first British use of gas did not have a favourable wind and affected over 2000 of the advancing Allied soldiers, some while still in their defensive trenches. The battles involved many reversals for both sides and troop losses were heavy (though less than the later Battle of the Somme). French was given much of the blame for this, despite previously noting the difficult terrain and need for more reinforcements and more artillery and munitions.

Soon after Loos, the Prime Minister demanded his resignation and Douglas Haig, once his trusted subordinate, but more recently a harsh critic, replaced him.

French returned to England to be appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Forces. During this command the 1916 Easter Rising occurred in Ireland. In 1918 French agreed to become Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. French was convinced that the Sinn Féin leaders had little support amongst the majority of the Irish people. He wanted Home Rule to be implemented, provided the violence was stopped first. He set up an Advisory Council, which he hoped might have representatives of all strands of Irish opinion, but in practice its members were all well-connected wealthy men and Sinn Féin were not involved. In 1918 French urged that a "Comrades of the Great War (Ireland)" be set up to look after returning Irish war veterans, to provide cash and land grants and also prevent them joining the Sinn Féin-dominated "Soldiers' Federation". This plan was stymied by cash shortage and inter-departmental infighting. The situation in Ireland continued to deteriorate and French resigned as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland on 30 April 1921.

French wrote a book after press attacks in 1917, titled 1914: The Early Campaigns of the Great War by the British Commander. The book was ghost written for him by the journalist Lovat Fraser and published in April and May 1919. There was criticism by contemporaries that the book was inaccurate.

Opinions of him varied from one extreme to the other. He was—at least during the Boer War—idolised by the public and during the First World War was reportedly loved by his men in a way that Douglas Haig never was. Churchill (in Great Contemporaries) wrote that French was "a natural soldier" who lacked Haig’s attention to detail and endurance, but who had "deeper military insight" and "would never have run the British army into the same long drawn-out slaughters". Haldane thought he had "been a great Commander-in-Chief, a soldier of the first order, who held the Army as no other could". Lloyd George praised him as "a far bigger man" than Haig and regretted that he "had fallen by the daggers of his own colleagues".

Edward Spears, a subaltern liaising between French and Lanrezac early in the war, later wrote of French: "You only had to look at him to see that he was a brave, determined man ... I learnt to love and to admire the man who never lost his head, and on whom danger had the effect it has on the wild boar…”.

His modern biographer Richard Holmes wrote that "he remains … a discredited man" but "history has dealt too harshly" with him. He argues that French was an emotional man who was deeply moved by casualties and identified too closely with his soldiers. Even a later critic Smith-Dorrien, informed the King's adviser Wigram (6 November 1914) that in situations where other men would have panicked "Sir John is unmoved and invariably does the right thing"). Holmes acknowledges that French's qualities were marred by his "undisciplined intellect and mercurial personality", but concludes by quoting Churchill's verdict that "French, in the sacred fire of leadership, was unsurpassed".

French was severely criticised by those close to Haig. The Official Historian Edmonds called him "only 'un beau sabreur' of the old fashioned sort—a vain, ignorant and vindictive old man with an unsavoury society backing" and claimed that French once borrowed Sir Edward Hamley's Operations of War from the War Office library but could not understand it (this seems unlikely given French was reportedly an avid reader of Dickens and other works, and that others have noted he read many military books and remembered enough of Hamley's doctrines not to take shelter in Maubeuge after the Battle of Mons,).

John French died on May 22nd, 1925. He was cremated and escorted by a military procession of six battalions of infantry, one battery of artillery, eight squadrons of cavalry and a detachment from the Royals to Victoria Station en route to his burial at Ripple. Before the funeral, an estimated 7,000 people filed past his coffin during the first two hours it lay in state, many of them veterans of the retreat from Mons. His pall bearers at the Westminster Abbey funeral included Haig, Robertson, Hamilton and Smith-Dorrien (who had travelled from France to pay his respects to a man with whom he had clashed badly).