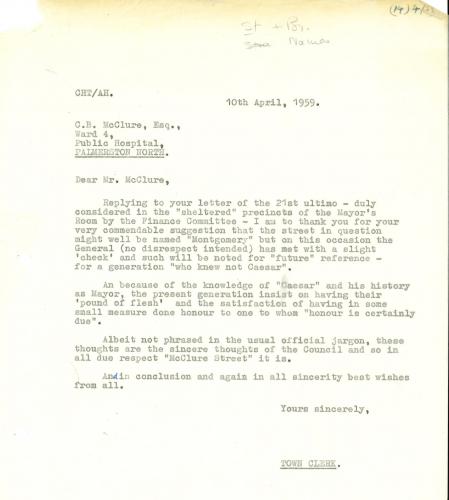

Mayor Cecil McClure, MC and Bar with Queen Elizabeth 1954

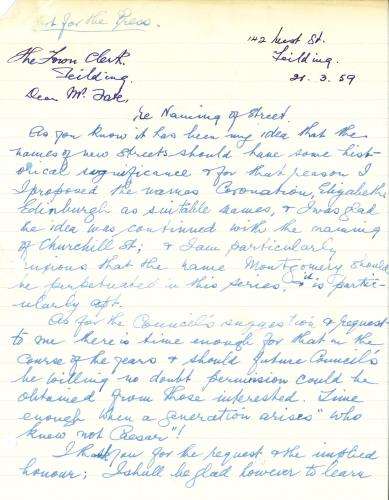

Reason for the name

McClure Street in Feilding is named after Captain Cecil B McClure BA, MC and Bar, Otago Infantry Regiment. He was Mayor of Feilding District Council for 10 years.

McClure Street in Feilding, is named after Captain Cecil B McClure BA, MC and Bar, Otago Infantry Regiment. He served in World War 1, firstly as a sergeant medical orderly on the NZ Hospital Ship Maheno off Gallipoli during the Dardanelles campaign and then as an infantry officer in France where he was twice decorated with the Military Cross; the first at Passchendaele and the second at Rossignol Wood. He was a teacher and eventually Mayor of Feilding District Council for 10 years.

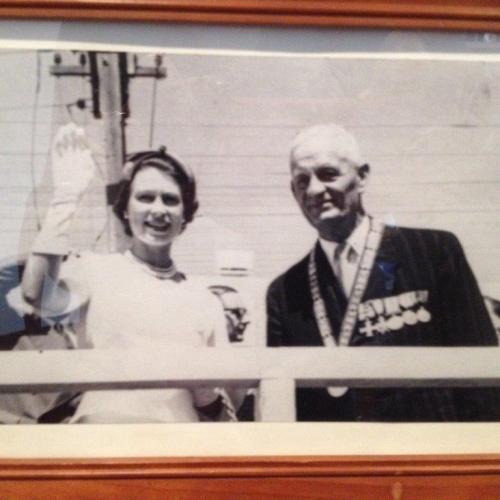

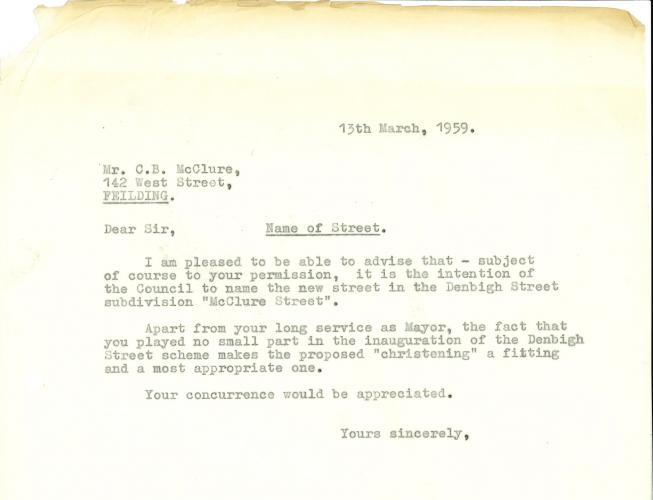

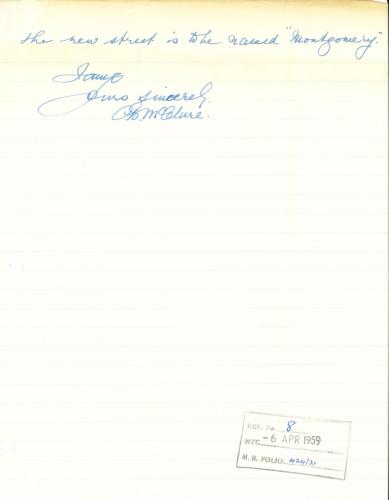

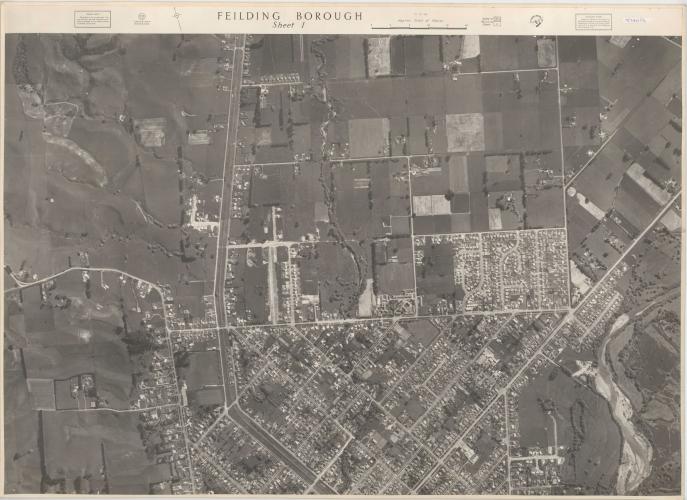

McClure Street lies in the north-west sector of Feilding, running off of Lethbridge Street and taking a right dog-leg shape to Homelands Avenue. The street was constructed as part of the Denbigh Street subdivision from 1959 to 1963. Feilding Borough Council correspondence series records reveal a series of letter from the Town Clerk to C B McClure. One of these, dated 13th March 1959, states the reason for commemoration of the new street:

"I am pleased to be able to advise that – subject of course to your permission, it is the intention of the Council to name the new street in the Denbigh Street subdivision “McClure Street”.

Apart from your long service as Mayor, the fact that you played no small part in the inauguration of the Denbigh Street scheme makes the proposed “christening” a fitting and a most appropriate one."

Although McClure expressed hesitation in being so recognised, he stated in a letter dated 22 December 1960 that he was honoured to, “share with ex-Mayors Carthew, Seddon, Ongley, Tingey, Fair, Taylor & others”.

Author (Biography): Patrick McClure, AO – Chairman, Oak Tree

Co-Author (Street Naming): Evan Greensides – Senior Archivist, Archives Central

About Sergeant Medical Orderly and Captain Cecil B McClure, MC and Bar, Otago Infantry Regiment NZEF

Cecil Bertram McClure was born on September 25, 1886 in Thornbury, Southland. He was one of nine children born to William and Agnes McClure. Cecil’s father William was a teacher and to progress his career the family moved to Gisborne where William became a headmaster. Cecil attended Gisborne Primary School and won a scholarship to Gisborne High School where he was captain of the rugby and cricket teams. In 1902 he passed the NZ Matriculation Exam and became a teacher. At age 24 years he enrolled in Knox College at Otago University to pursue studies for the ministry. He represented Otago University and Otago Province in hockey and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts.

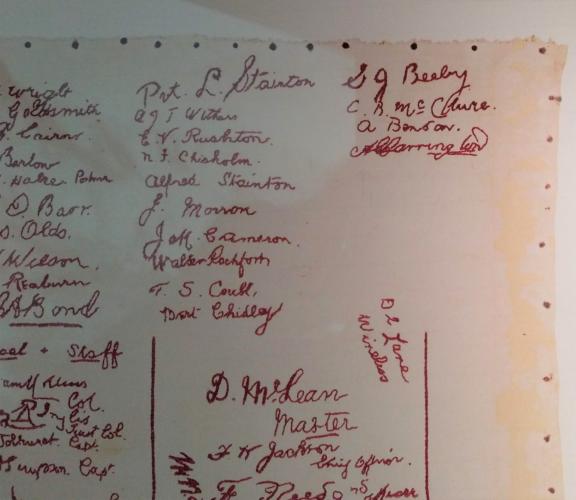

Shocked by news of heavy casualties in the NZ Expeditionary Force after the Anzac landing at Gallipoli, Cecil volunteered as a medical orderly on the NZ Hospital Ship “Maheno”. He served on the hospital ship from 7 July, 1915 to 1 January, 1916. They took wounded NZ soldiers off Anzac Cove and provided medical assistance as well as transporting the seriously wounded to Lemnos Island where there were tent hospitals. In his diary note of 27 August, 1915 he writes: “Altogether 600 men attended to. Over 100 returning to beaches as wounds were less serious. One case: shattered arm, bullets in head, wrists, ankles, shoulder and hips. Others I can’t write down. The ship is literally a bloody mess.”

He then returned to New Zealand and volunteered to join the NZ Expeditionary Force. He served from 10 February, 1916 to 23 November, 1919. He was promoted to Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion, Otago Regiment and fought in the major battles of Messines, Ypres, Passchendaele, Rossignol Wood and Bapaume on the Western Front.

Cecil wrote letters home to his family describing his experiences. The following letter is about the battle of Messines where the Anzacs scored a stunning victory. The Messines ridge in Belgium is close to the border with France. German defences consisted of an elaborate system of well-wired trenches over two kilometres. The ridge had machine gun emplacements in concrete pill-boxes which protected them from artillery fire. The Germans thought Messines could not be captured.

Zero hour, the opening moment of the attack, was on June 7, 1917. At 3.10am 500 tons of underground mines were set off and mass artillery was fired along the line. Within an hour, the New Zealanders had captured Messines. By evening the Allies had taken 7000 prisoners. The destructive force of the mines and artillery and the rapidity of the infantry attack overwhelmed the Germans and led to the capture of the stronghold of the Messines Ridge in one day.

Cecil describes his experience in a letter sent home to his family:

“For the last few days I have been having my experience of real warfare and I don’t know what to say. Digging, fighting, starving, shell-fire, explosives, machine gunfire, thrilling, death-defying moving from one spot over shell-ploughed ground to another still more dangerous. Sleepless nights in a shell hole, bandaging the wounded, giving water to those in need, chasing prisoners through the lines were all incidents in one day which has no comparison outside warfare.

Where or when could any human being see his men hit with explosive shells and yet deliberately march on with the remainder, leaving the wounded to their fate? What kind of man would pass wounded men crying for water, ignoring them apparently as if it were no concern of his? How can men deliberately walk into a hail of bullets and showers of shrapnel seeking only the lives of others? Why do men choose such hell as battle? Yet all these things have been my experience. To anyone, except those who have been in battle, they have no meaning, no matter how vivid the imagination.

That experience of ‘going over the bags’ was different from anything I have ever known. Leaping out of protection into open country and calmly marching across trenches and shell-pitted ground. Scrambling through barbed wire obstacles and ditches; climbing the hill on the other side of the swamp, while all the time accompanied by bullets, shells, bursting shrapnel and loud explosions was played by our men behind machine guns and cannons.

While we lay huddled in our trenches, there was suddenly a deadly calm and anxiously we awaited that awful explosion which also meant our advance. Without warning the earth seemed to open, the ground rocked and the sky was blotted out with an awful glare as guns of every size fired with unimaginable noise.

Were we to go out into this? Was this where we left our protective trench and faced – we knew not what? Now for it! Over the top we go. All is strange and the atmosphere is full of dust, smoke and smell of powder. The light is also obscured by this smoke and we stumble forward. Here was an unpassable trench. Now the wire is cut. There are men of two other companies mixed up with us. I could not find some of my men, but through a hedge we went and over a ditch. The order was “Dig in”. In a few minutes all our boys were with us and on our flanks the daylight revealed men digging feverishly from shell hole to shell hole. In two hours they were down seven feet and in comparative safety. However several times a shell falling nearby would bury one or two men.

A German barrage fell heavily near our machine guns and three of the boys went down. Then the machine guns began the slaughter of our men. In twos they came into my shell hole with terrible wounds. As soon as they were bandaged, their wounded comrades assisted them to the dressing station. Never in my life have I known exhaustion as I knew it then. I was so dry and scorched that I could not eat lunch. I took a bite of dry bread but almost choked in trying to swallow it. I had foolishly emptied my water bottle giving water to the wounded and one poor German officer who was almost dead. When I returned after crossing the whole of the remains of Messines and vicinity I was absolutely exhausted. If I felt that way, what about the boys who had no less than two separate turns of digging for three hours each time!

Then the prisoners and wounded arrived. The Germans simply ran down the hill, hands aloft, shouting “kamerad, kamerad!” The first group of twenty we put to digging the trench and their willingness was almost comical. Maybe they guessed the Sergeant Major’s intention of shooting them. The only way we could save them from the boys’ vengeance was the offer that it would be better to hand them over to the wounded to march them back.

It is useless my attempting to tell more on paper. So wonderful, so strange, so cruel, so grand a battle! So awful the death! So appalling that man could do this thing, so glorious a fight, so sad and sorrowful a day for many! No pen of mine could describe the immensity of the destruction, the cruelty, the glory and damnation of war! I can only repeat what I said when I first saw the wounded at Anzac Cove: Grant to us peace in our time, O Lord.”

Cecil was awarded the Military Cross at Passchendaele on 12 October 1917. The citation reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He led his platoon with great dash and gallantry, under heavy machine gun fire, and was wounded in an attempt to get through the enemy's wire. His cheerfulness and coolness did much to encourage his men under heavy fire.”

He was awarded a Bar to the Military Cross on 25 July, 1918 at Rossignol Wood, France. The citation reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He led his men during an attack and consolidated the captured position, under heavy fire, with conspicuous gallantry. During the counter attack, by skilful leadership, he was the means of capturing many prisoners and preventing the enemy from obtaining a footing in our line. He set a fine example to all.”

After the War

Cecil returned to New Zealand and married Nancy Hood. Over time he adopted her two children, Arthur and Roma. They moved as a family to Masterton where Cecil was a college master at the newly opened Wairarapa High School. When Arthur left home to go to University in Wellington, Cecil wrote him a letter. In the course of it he said:

“No individual can live for himself. His influence is ever widening like the eddies from a stone thrown into a pond. He touches the lives of others at many points and influences many characters where he least suspects his influence. Your life is held in trust by you that you may use it to best advantage for your own good, the good of others and the good of society”

Cecil was promoted to Deputy Headmaster of Feilding Agricultural High School and he taught there for 25 years until his retirement. For years he was coach of the 1st XV and Ist XI teams. His popular leadership, war record and prominent Roman nose resulted in the boys giving him the nickname “Caesar”.

His life took a new turn when he entered local politics and was elected a Councillor on the Feilding Borough Council. He was an elected councillor for 20 years. In 1947 Cecil was elected Mayor of Feilding Borough Council. He revelled in this new leadership role in the community and remained mayor for 10 years and four successive terms of office.

In 1952 Cecil and Nancy McClure welcomed the Governor-General of New Zealand, Sir Bernard Freyberg V.C. and Lady Freyberg on a visit. In 1954 they welcomed Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh when they visited on their Royal Tour of New Zealand. In 1955 Cecil laid the foundation stone for the Feilding Civic Centre which he officially opened. Some of the locals recalling his nickname “Caesar” called it “Caesar’s Dream House.” Over the years he represented the town at official functions and events.

In 1960 Cecil and Nancy moved to Auckland to be close to their family. They bought a house in Epsom and lived out their remaining years there. He died in 1966 and Nancy four years later.

Cecil B McClure lived a full life. He volunteered as a medical orderly on the NZ Hospital Ship “Maheno” caring for wounded soldiers at Anzac Cove. He fought with the NZEF in the major battles of the Western Front and for his leadership and courage was awarded the Military Cross and Bar. He married Nancy and adopted her two children, Arthur and Roma. He had a career of service as a teacher and Deputy Headmaster of Feilding Agricultural High School. He was elected Mayor of Feilding Borough Council for 10 years. He was loved and respected by a large circle of friends