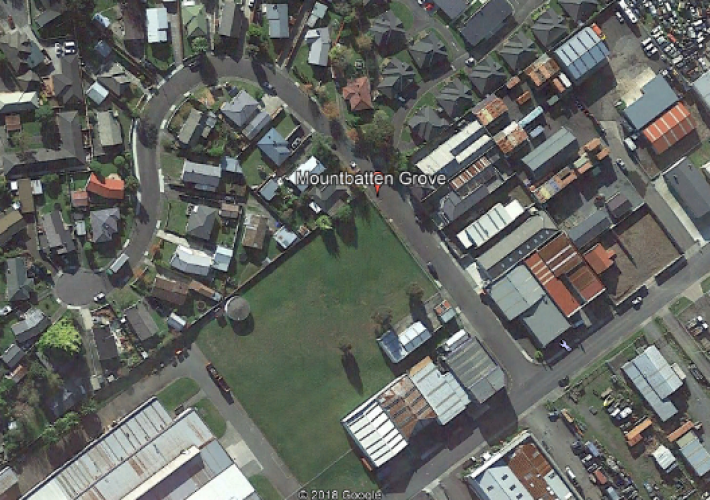

136 Mountbatten Grove Upper Hutt, street view 2018

Reason for the name

There are three streets in an Upper Hutt industrial area named after World War 2 senior leaders; Montgomery Crescent, Mountbatten Grove and Cunningham Road. These three British senior Officers were involved with New Zealand forces throughout the war.

Admiral of the Fleet, The Right Honourable The Earl Mountbatten of Burma KG GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO PC FRS

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, KG, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCIE, GCVO, DSO, PC, FRS (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British Royal Navy officer and statesman, an uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and second cousin once removed of Queen Elizabeth II. During the Second World War, he was Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command (1943–1946). He was the last Viceroy of India (1947) and the first Governor-General of independent India (1947–1948).

From 1954 to 1959, Mountbatten was First Sea Lord, a position that had been held by his father, Prince Louis of Battenberg, some forty years earlier. Thereafter he served as Chief of the Defence Staff until 1965, making him the longest-serving professional head of the British Armed Forces to date. During this period Mountbatten also served as Chairman of the NATO Military Committee for a year.

In 1979, Mountbatten, his grandson Nicholas, and two others were assassinated by a bomb set by members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, hidden aboard his fishing boat in Mullaghmore, County Sligo, Ireland.

Author: Poppy Places Trust

When war broke out in September 1939, Mountbatten became commander of the 5th Destroyer Flotilla aboard HMS Kelly, which became famous for its exploits. In late 1939 he brought the Duke of Windsor back from exile in France and in early May 1940, Mountbatten led a British convoy in through the fog to evacuate the Allied forces participating in the Namsos Campaign during the Norwegian Campaign.

On the night of 9–10 May 1940, Kelly was torpedoed amidships by a German E-boat S 31 off the Dutch coast, and Mountbatten thereafter commanded the 5th Destroyer Flotilla from the destroyer HMS Javelin. He rejoined Kelly in December 1940, by which time the torpedo damage had been repaired.

Kelly was sunk by German dive bombers on 23 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete; the incident serving as the basis for Noël Coward's film In Which We Serve. Coward was a personal friend of Mountbatten and copied some of his speeches into the film. Mountbatten was mentioned in despatches on 9 August 1940 and 21 March 1941 and awarded the Distinguished Service Order in January 1941.

In August 1941, Mountbatten was appointed captain of the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious which lay in Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs following action at Malta in the Mediterranean in January. During this period of relative inactivity, he paid a flying visit to Pearl Harbour, three months before the Japanese attack on the US naval base there. Mountbatten, appalled at the base's lack of preparedness, drawing on Japan's history of launching wars with surprise attacks as well as the successful British surprise attack at the Battle of Taranto which had effectively knocked Italy's fleet out of the war, and the sheer effectiveness of aircraft against warships, accurately predicted that the US entry into the war would begin with a Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbour.

Mountbatten was a favourite of Winston Churchill. On 27 October 1941 Mountbatten replaced Roger Keyes as Chief of Combined Operations and was promoted commodore. His duties in this role included inventing new technical aids to assist with opposed landings. Noteworthy technical achievements of Mountbatten and his staff include the construction of "PLUTO", an underwater oil pipeline from the English coast to Normandy, an artificial harbour constructed of concrete caissons and sunken ships, and the development of amphibious tank-landing ships. Another project that Mountbatten proposed to Churchill was Project Habakkuk. It was to be a massive and impregnable 600-metre aircraft carrier made from reinforced ice ("Pykrete"): Habakkuk was never carried out due to its enormous cost.

As commander of Combined Operations, Mountbatten and his staff planned the highly successful Bruneval raid, which gained important information and also captured part of a German Würzburg radar installation and one of the machine's technicians on 27 February 1942. It was Mountbatten who recognized that surprise and speed were essential to ensure the radar was captured, and saw that an airborne assault was the only viable method. He was in large part responsible for the planning and organisation of The Raid at St. Nazaire in mid-1942, an operation which put out of action one of the most heavily defended docks in Nazi-occupied France until well after war's end, the ramifications of which contributed to allied supremacy in the Battle of the Atlantic. After these two successes came the Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942. He was central in the planning and promotion of the raid on the port of Dieppe. The raid was a marked failure, with casualties of almost 60%, the great majority of them Canadians. Following the Dieppe raid Mountbatten became a controversial figure in Canada, with the Royal Canadian Legion distancing itself from him during his visits there during his later career. His relations with Canadian veterans, who blamed him for the losses, "remained frosty" after the war.

Mountbatten claimed that the lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid were necessary for planning the Normandy invasion on D-Day nearly two years later. However, military historians such as former Royal Marine Julian Thompson have written that these lessons should not have needed a debacle such as Dieppe to be recognised. Nevertheless, as a direct result of the failings of the Dieppe raid, the British made several innovations, most notably Hobart's Funnies – specialized armoured vehicles which, in the course of the Normandy Landings, undoubtedly saved many lives on those three beachheads upon which Commonwealth soldiers were landing (Gold Beach, Juno Beach, and Sword Beach).

In August 1943, Churchill appointed Mountbatten the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Command (SEAC) with promotion to acting full admiral. His less practical ideas were side-lined by an experienced planning staff led by Lieutenant-Colonel James Allason, though some, such as a proposal to launch an amphibious assault near Rangoon, got as far as Churchill before being quashed.

British interpreter Hugh Lunghi recounted an embarrassing episode which occurred during the Potsdam Conference, when Mountbatten, desiring to receive an invitation to visit the Soviet Union, repeatedly attempted to impress Josef Stalin with his former connections to the Russian imperial family. The attempt fell predictably flat, with Stalin dryly inquiring whether "it was some time ago that he had been there". Says Lunghi, "The meeting was embarrassing because Stalin was so unimpressed. He offered no invitation. Mountbatten left with his tail between his legs."

During his time as Supreme Allied Commander of the Southeast Asia Theatre, his command oversaw the recapture of Burma from the Japanese by General William Slim. A personal high point was the receipt of the Japanese surrender in Singapore when British troops returned to the island to receive the formal surrender of Japanese forces in the region led by General Itagaki Seishiro on 12 September 1945, codenamed Operation Tiderace. South East Asia Command was disbanded in May 1946 and Mountbatten returned home with the substantive rank of rear-admiral. That year, he was made a Knight of the Garter and created Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, of Romsey in the County of Southampton as a victory title for war service.

Following the war, Mountbatten was known to have largely shunned the Japanese for the rest of his life out of respect for his men killed during the war, and as per his will, Japan was not invited to send diplomatic representatives to his funeral in 1979, though he did meet Emperor Hirohito during a state visit to Britain in 1971, reportedly at the urging of the Queen.

Assassination

Mountbatten usually holidayed at his summer home, Classiebawn Castle, in Mullaghmore, a small seaside village in County Sligo, Ireland. The village was only 12 miles (19 km) from the border with Northern Ireland and near an area known to be used as a cross-border refuge by IRA members. In 1978, the IRA had allegedly attempted to shoot Mountbatten as he was aboard his boat, but "choppy seas had prevented the sniper lining up his target".

On 27 August 1979, Mountbatten went lobster-potting and tuna fishing in his 30-foot wooden boat, Shadow V, which had been moored in the harbour at Mullaghmore. IRA member Thomas McMahon had slipped onto the unguarded boat that night and attached a radio-controlled bomb weighing 50 pounds. When Mountbatten was aboard, just a few hundred yards from the shore, the bomb was detonated. The boat was destroyed by the force of the blast, and Mountbatten's legs were almost blown off. Mountbatten, then aged 79, was pulled alive from the water by nearby fishermen, but died from his injuries before being brought to shore. Also aboard the boat were his elder daughter Patricia (Lady Brabourne), her husband John (Lord Brabourne), their twin sons Nicholas and Timothy Knatchbull, John's mother Doreen, (dowager) Lady Brabourne, and Paul Maxwell, a young crew member from County Fermanagh. Nicholas (aged 14) and Paul (aged 15) were killed by the blast and the others were seriously injured. Doreen, Lady Brabourne (aged 83) died from her injuries the following day.